[working title]

[working title]

May - June, 2000

Stanley Picker Gallery,

Kingston University,

Kingston Upon Thames

Curated by Susanne Clausen & Alun Rowlands

Johnny Spencer, Winston Churchill as a Painter, 1995-96

Laminate, paper on panel, 81 x 57 cm

(courtesy Anthony Wilkinson Gallery)

Johnny Spencer, The Artist - Adolf Hitler, 1995-96

Laminate, paper on panel, 81 x 57 cm

(courtesy Anthony Wilkinson Gallery)

This work is part of a series by Johnny Spencer whose work featured in the British Art Show of 2000. They present research into aspects of our social and cultural life - from hairstyles to economic groups. Information is gathered from a wide range of sources and re-presented as an authoritative examination of the subject —‘The Poor’, ‘The Mouflom’ ‘Coffee Tables’ ‘Incarceration’. These works raise questions about academic practice and the way that we collect information to define and theorise both small and vast areas of experience.

Inventory is a collective enterprise set up by a group of writers, artists and theorists looking to explore the alternatives to the limitations imposed on these disciplines. Inventory operates on a number of fronts ranging from a regularly published journal (‘Inventory’) to organized events, lectures, interventions and exhibitions. Inventory proclaim a sociological trawl through the city. In acts of re-appropriation, found objects are modified, altered, written upon and carved into and the street becomes the site for defiant interventions. Acts of subjective and collective resistance to established order rally against alienated existence, consumer culture, and the regimentation of urban space. Inventory’s work exists primarily as an agitational force, concerned with ideas, content, and communication, creating an enthused writing that penetrates the marginal and the everyday, the theoretical and the sensorial, for a readership that refuses to be crushed by this meagre existence.

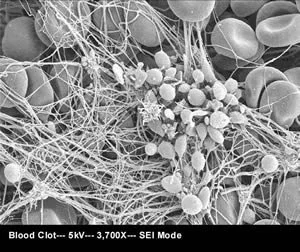

Excerpts from videos of their public action Coagulum (2000), in which a group of individuals suddenly assemble into a sort of rugby scrum formation, inside a local shopping mall —Coagulum.

‘We have no desire to transform social life into art or vice versa. In a manner similar to that of a strike, our Coagulum is a refusal of our role, of our work as consumers. Play flouts work - it produces nothing other than itself. It is a paroxysmal movement that produces nothing but its own energy - which it expends uselessly. Coagulum is a siege machine for infecting organisational space. Building more transitory micro communities, accelerating a process whereby sociality begins to assert itself, seizing and squandering human energies.’

—Inventory (excerpt from Coagulum, Inventory, Vol.4 No.1, 2000)

[working title] brings together artists whose practices question how art can act within, and against, the systems that produce it. This exhibition revisits experiments in self-organisation, critical fiction, and social play. It asks what forms of agency might still be possible for art when its institutional critique has already been absorbed by the institution itself.

Liam Gillick’s The Winter School (1997) inhabits this same tension. Printed as an offset poster, the work revisits 1971 from the perspective of 1996. Gillick imagines a school that might have been — a collective structure for thinking and reformation. The text alternates between recollection and speculation, treating “school” as both memory and model, as a shifting form for shared production. Gillick’s modest print becomes a proposal —that education can exist outside institutional walls, in temporary, revisable forms of assembly.

Alexander Brener and Barbara Schurz’s book Demolish Serious Culture!!! (2000) asserts that seriousness itself has become a form of paralysis: “Seriousness is a freezer with cadavers in it and the not-serious is a rotting flower.” Their provocation opens a space between renunciation and renewal —a refusal of the moral weight that often freezes political and cultural discourse. For Brener and Schurz, the not-serious is not apathy —it is an act of resistance, a strategy of refusal against the deadly seriousness of cultural orthodoxy.

Tilo Schulz’s E.W.E – exhibition without exhibition (1999) expands this notion of the exhibition as a distributed network of thought. This project has travelled across Europe as a lecture-performance, accompanied by a set of artist pamphlets in a blue binder. The usual apparatus of exhibition — catalogue, poster, lecture — became the exhibition itself. By displacing the show into its supporting structures, Schulz and his collaborators blur the line between presentation and mediation. The result is both a critique and a reinvention of the curatorial form, one that foregrounds the circulation of ideas rather than their visual consolidation.

Johnny Spencer’s series of laminated prints, including Winston Churchill as a Painter (1995–96) and The Artist – Adolf Hitler (1995–96), extend this critical approach to the production of knowledge. Spencer’s works parody the forms of academic research — classification, typology, and authority — to expose how culture constructs its categories. Spencer’s “research” into artists, politicians, or social groups uses data and imagery to mimic objective study, while revealing its ideological underpinnings. In doing so, he collapses distinctions between scholarship and satire, seriousness and absurdity.

Inventory situate their practice directly in the street. Guided by Walter Benjamin’s phrase “the inventory of the street is inexhaustible,” they conduct interventions that disrupted the rhythms of everyday life. Coagulum (2000) is a spontaneous scrum of bodies inside a Kingston shopping mall rejecting both the role of artist and the role of consumer. The performance is an act of refusal, “a siege machine for infecting organisational space.” Inventory’s journal serves as both record and manifesto, fusing theoretical writing with anarchic energy. Their work recalls Situationist tactics, and reclaims them for the late capitalist metropolis — where even dissent risks being commodified.

Salon de Fleurus offers a different mode of reconstruction. Re-creating Gertrude Stein’s Paris salon, once a cradle of modernity, through painted reproductions and staged interiors. By remaking the salon as a fictional space, the project reveals how art history itself is built on acts of copying, storytelling, and myth-making. The salon’s simulacrum become more telling than the originals, exposing how modernism’s narratives were curated, circulated, and domesticated. We encounter not authenticity, but its performance — a self-aware history lesson that questions the museum’s claim to truth.

Henriette Heise and Jakob Jakobsen’s Info Centre (1998–99) continued this institutional questioning. Info Centre transformed an office space into a hybrid reading room, archive, and meeting point. Visitors could browse artists’ publications, drink home-brewed beer, and engage in informal discussion. Info Centre was a deliberate act of “self-institutionalisation,” — the creation of an institution for alternative practice. Rather than reject structures altogether, they proposed new ones —flexible, accessible, and sustained by collective care. Their project anticipates debates around art’s social responsibility and the politics of access.

Volker Eichelmann, Jonathan Faiers, and Roland Rust’s Do You Really Want It That Much… More! (1998) turns the lens toward the cinematic museum. Their crash edited video compilation of film scenes set in art galleries exposes how popular culture imagines these spaces —as sites of romance, crime, and spectacle. Through montage, they show the museum as both fortress and stage, a place of forbidden desires and social codes. The work asks why cinema repeatedly transforms the museum into a theatre of excess. It reveals the institution’s double role as a space of reverence and a screen for projection.

[working title] revisits artistic practices that refuse to remain confined within the gallery, acknowledging the paradox of “critical” forms, which simultaneously absorb critique. These projects use fiction, publication, performance, and self-organisation as tools to unsettle the hierarchies between artist, curator, and publics. [working title] is an ongoing possibility — the exhibition embraces incompletion as a method. It understands that the institution cannot be simply rejected or redeemed. It must be continually reimagined from within. The ‘work’ suggest that the task of art today is not to demolish the institution, but to keep it in motion — to treat it as a provisional fiction sustained by the people who use it.Through these reassembled fragments, [working title] stages both memory and rehearsal, a re-encounter with past gestures of resistance, and a renewed invitation to invent new ones.

Alexander Brener & Barbara Schurz //

Mark Dickenson & Martin Clarke //

Volker Eichelmann, Jonathon Faiers & Roland Rust //

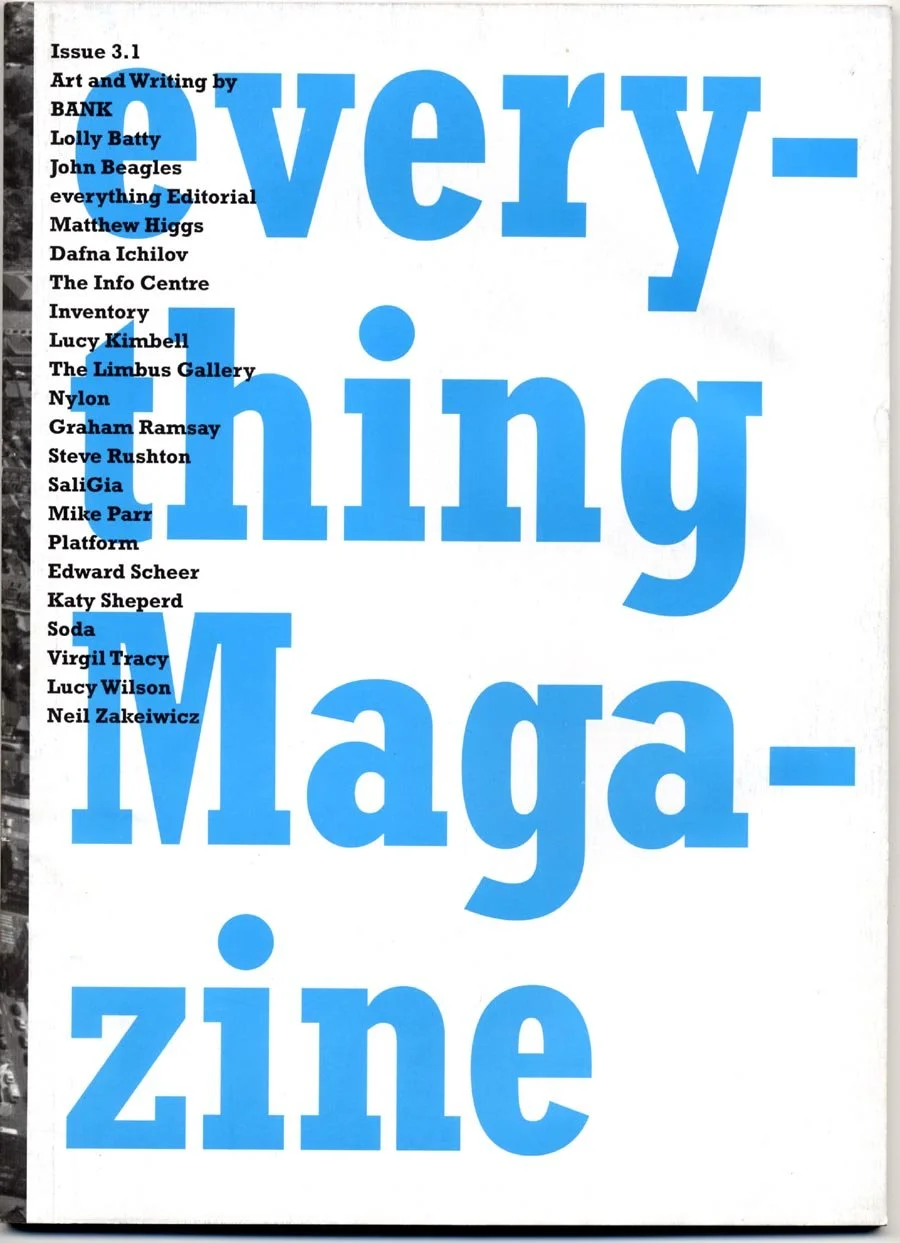

everything Editorial //

Alec Finlay //

Salon de Fleurs //

Liam Gillick //

Henriette Heise //

Inventory //

Tilo Schulz //

Jakob Jakobsen //

Pavlo Kerestey //

Johnny Spencer //

Szuper Gallery //

Markus Vater //

Christopher Warmington //

Info Centre, London (1998–1999), a hybrid between an exhibition venue, bookstore, and archive.

Salon de Fleurus is an artwork, a contemporary reconstruction of Gertrude Stein’s Parisian salon that existed at 27 rue de Fleurus from 1904-34. It is a work that displays and references a story of modern art’s origins through one of the first gathering places for burgeoning artists such as Matisse, Picasso, and Stein herself. It was in Stein's salon that paintings by Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso were seen exhibited together for the first time both by her peers and transatlantic art experts who spread the word back home, eventually creating the American narrative of European modern art familiar today.

Through painted reproductions exhibited within a constructed interior, the Salon de Fleurus questions where, why and how certain narratives of modern art originated through the salon structure that first canonized them. These copies are perhaps more significant and tell us more about history than the original artworks themselves by weaving fiction into history and leaving space to contemplate and reconsider the past. When one looks at Picasso here, they are viewing Picasso through the lens of Stein.

Beginning in 1992 Salon de Fleurus exists as a semi-private salon in lower Manhattan. It has appeared in fragments in Beirut, Paris and Los Angeles. The exhibition contains painting reproductions as well as a historic timeline of Stein and her circle, and training script for a “doorman” or gallery monitor to best evoke the story of the salon to visitors.

Info Centre, a project space in East London by Henriette Heise & Jakob Jakobsen.

The first info sheet of the Info Centre stated: “We are committed to an understanding of art practice that is not exclusively related to the making of art works, but also includes the establishing of institutions for the experience and use of art and generally the making of institutions for human life.”

Info Centre attests to the need to institutionalise alternatives in order to care for them. The refusal to support alternative practices with the institutions that they need and deserve to thrive. We do not need to avoid institutionalisation, we need fuller, wider, and more diverse forms of institutionalisation. Institutionalisation for the few needs to be replaced by institutionalisation for all.

Liam Gillick (*1964), The Winter School, 1997, Offset print two colours, 42 × 60 cm, Edition. 200

“Last year. 1996. A winter scenario. Before the main event. A moment spared for thinking back to another time. 1971. A new structure could have been created, a kind of school.”

The work alternates between recollections of 1971 and reflections on 1996, drawing parallels about reinvention, collective knowledge, and the meaning of a "school" beyond traditional forms.

Markus Vater, Her hands smell of architecture, 2000

Interview

Hans-Ulrich Obrist: Lets begin with the beginning. Because the first time I heard about it was when I got this very puzzling and personal- impersonal postcard signed by someone I did not know which arrived towards the end of last year. How did it all start? I would then like to know about the project, about the history of how the collaboration started, how the two of you met. Both of you have been working in sort of different collaborations with different artists. (1)

[working title]: We were both aware of each other's involvement in Szuper Gallery and Arthur R. Rose respectively. Working within the same institution placed us both in a position whereby we had an opportunity to realise our various discussions. The gallery offered a site that was generic, new, executive and geographically peripheral. We wanted to transform its prosaic existence through offering it as a support system for personal engagement, production of new work and to address the models by which we recognise art. We attempted to pass over the burden of former concerns in favour of building a more relaxed, complex relationship with art, society and audience. Within this approach there is no either/ or between the gallery/ institution and any other context. Institutional critique and its contiguous discourses have washed up and been absorbed. Here, it is no longer wearily aggressive but has an elasticity and social sensibility. We think this fluency allows collaboration as the work functions and reaches its audience by piggy backing the existing institution. This was established early on in our initial meetings.

Maria Lind: At this first meeting did you already discuss how you would work together, what kind of method you would use? (2)

[working title]: Our prevailing attitude in forming this situation was to fictionalise the series of relations constructed. This use of fiction appears as a diversion from the object while trying to promote discussion and produce something more solvent. Our conversations centred on introducing artists and work to reach points of agreement or contestation. The exhibition would always remain a 'possibility', mutating and drifting across the rules that govern the demarcation of the model, before disappearing.

Rosetta Brooks: It seems symptomatic of an artistic climate withdrawing from the world and making the [gallery] immediate reality of one's art. Is this just a reaction to a depressing situation…? (3)

[working title]: It could be suggested that the routine task of the artist is to bring forth objects for perusal, representation and possible acquisition by collectors. The endless intention to produce and supply has resulted in saturation, monotony and homogeny. [working title] discloses how some artists are persistently looking to be active and precipitate change across a social and political field. We think that many of works and projects highlight the fragile nature of the narrative structures we use to support our own beliefs. The gallery or institution, therefore, becomes just another vector within the imaginary. The various projects work as independent constructions, with a separate chronology, subjective conditions and, paradoxically, stand for an inevitable deficiency… The artists involved often require public participation in the production of the work that centres their practice at the interces of invention and reception. This locality is not dominated by the need to legitimise art for the marketplace, where authorship is unimportant and exchange value almost non-existent.

Francesco Bonami: Art, in a sense, is obsolete. It is slow to be updated, especially since, at the end of the day, the same criteria and systems return to the fore… Do you think new institutions from outside can be grafted onto the contemporary art world? (4)

[working title]: It is, perhaps, difficult to grasp art beyond a matrix of socio-economic and historical contexts that dictate our codes of practice. The critical interventionist's of the 1970's led the way for the development of new dialogue and performative practices that engaged audiences in active reflection. Today, there has been a shift in character, a migration through invitation, from outside agitators to inside operators… Regarding 'speed' we can recognise that a number of projects are durational and necessitate a slower and more modest intrusion. This lack of speed in comparison with other societal systems, in some ways, is their strength. Simultaneously, mobility and navigation appear as vital qualities in locating positions and creating awareness within this territory…

Within [working title] there is evidence of resistance, through default, to an overriding order. Amidst the undercurrent, perhaps, we can operate as an interruptive device, a jolt, to the flow of things. [working title] does not propose that a new network will arise. It seeks to avoid established conventions in favour of some form of engagement that designates change.

……………………………….

1 Q. from 'Cities on the move: from Bangkok to Vienna in a tuk tuk' Hans Ulrich Obrist & Hon Hanru. p.1

2 Q. from 'Blind Date' converstaion between Susanne Gaensheimer, Maria Lind, Ann Lislegard & Olaf Nicolai. p.1

3 Q. from ZG. Issue 1. 1980

4 Q. from Flash Art, summer 1998. Giancarlo Politi & Helena Kontova talk with Francesco Bonami. p.101

Tilo Schulz, E.W.E exhibition without exhibition, 1999

5 v. Paperback, Offset printed, Edition 750

This exhibition catalogue is for the Leipzip, Germany show entitled “E.W.E: exhibition without exhibition,” in which the items that normally surround a show - postcards, posters, previews, publication and lecture tour details - become the centre of attention. Artists Nathan Coley, Plamen Dejanov, Swetlana Heger, Jens Haaning, Sandra Hastenteufel and Olaf Nicolai each contribute a separate pamphlet to the catalogue which collects them in a blue folded binder.

Nathan Coley produced a small book as part of his ongoing By order of the king work. Olaf Nicolai produced the first of his stilleben-publications. Sandra Hastenteufel gave a different version of her space and other infinities-project for the lecture than the one she published in her booklet. Plamen Dejanov & Swetlana Heger produced an empty notebook. Jens Haaning used the structure of e.w.e. to advertise one of his own projects.

Jonathan Faiers, Volker Eichelmann, Roland Rust, Do You Really Want it That Much...more!, 1998

In the video installation “Do you really want it that much?” - “More!” Volker Eichelmann, Jonathan Faiers and Roland Rust present a compilation of feature film scenes of various genres set in the spaces of art museums or galleries.

Annotated by short texts and thematic headings, the artists create an image-rich portrait of art institutions - of their topography, the selected details of their furnishings, and the most diverse interests, often quite distant from art, with which they are entered. How are art spaces projected in mainstream cinema? What does cinema want to tell us about the function of these spaces? Why does the cinematic representation of museums and galleries differ so much from the real?

The result is revealing, as the social uses of these places clearly emerge. Unusual but often varied forms of entering or leaving a temple of art become apparent, sequences of amorous rendezvous are juxtaposed with those dealing with the theft of precious objects, backdrops of sophisticated vernissage banter are transformed into hiding places after a completed murder.

The museum is presented as an impregnable glittering fortress only to be reduced to a self-service shop window for the master criminal’s picking. These films subvert the museum’s function as custodian of the priceless cultural artefact. In many films the love of art is intermingled with the love of flesh. As in ‘Pleasure Seekers’ art spaces seem to provide the perfect stalking ground for sexual predators stimulated by the act of looking. With art spaces transformed into meeting places does the love of the object and the love object become irretrievably blurred?

Demolish Serious Culture!!!, 2000,

Alexander Brener & Barbara Schurz, Art, politics, culture, resistance, revolt, radical democracy and why ‘Seriousness is a freezer with cadavers in it and the not-serious is a rotting flower.' 202 pages, Paperback ISBN10: 385266148X