Wiring Diagram

Radical Conservatism,

Castlefield Gallery, Manchester

30 November 2013 - 02 February 2014

Curated by Pil and Galia Kollectiv

Symposium: Radical Conservatism

February 2014

Today more than ever, with the left increasingly holding on to the past of the welfare state as an ideal, and the right quietly revolutionising our world through neoliberal reforms, the paradigms of radicalism and conservatism need to be redefined. Can conservatism be seen as a radical position in itself? Join us for this symposium that will explore the themes of the Radical Conservatism exhibition.

Speakers include: Professor Alun Rowlands, curator, University of Reading; writer and art critic Robert Garnett and the curators of the Radical Conservatism exhibition Pil and Galia Kollectiv. The afternoon will also include a performance by artist Chris Evans.

Alun Rowlands, Blue Sky Thinking / Episode 4, 2002, 42 x 30 cm. In: 'Slimvolume Poster Publication', London, 2002. Image: V&A Prints and Drawing.

Slimvolume Poster Publication, 2002

includes work by a.o. Beagles and Ramsey, JJ Charlesworth, Martin Clark and Mark Dickenson, FlatPack001, Annabel Frearson, hobbypopMUSEUM, Elizabeth Kent, Tony Maas, Andrew Mania, Dave Muller, David Musgrave, Karin Ruggaber, Emily Jo Sargeant, Michael Wilson, Paul Harrison and John Wood.

Script for ‘Wiring Diagram’ talk at ‘Radical Conservatism’ symposium at Castlefield Gallery 2014. Radical Conservatism explores the space between two moments. Between the impulse to hold on and the desire to overturn. It asks whether these terms — radical and conservative — are really opposed at all.

In Britain, where the European avant-garde never truly took hold, a kind of reactionary modernism has long defined our culture — wary of revolution, suspicious of utopia. But today, the opposites are reversed. The question, posed by this exhibition, is not what is radical, but what is left to conserve. Can conservatism itself become a radical stance? And if art is defined by movement toward the new, could holding on to the past — stubbornly, deliberately — now be a critical position?

[Prologue]

”At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

I can only say, there we have been: but I cannot say where.

And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time.”

—T.S Eliot, 'Burnt Norton, (No. 1 of Four Quartets)’ 1936

Eliot loathed modernity.

What did he hope to conserve against its advance?

His poetry was revolutionary. And it was also conservative. His criticism explains this paradox. Originality emerges after assimilation of traditions.

A continually modified tradition is not an unchanging magisterium.

In politics and religion alike, Eliot’s conception of tradition is surprisingly dynamic. Our “danger,” he wrote, is “to associate tradition with the immovable; to think of it as something hostile to all change; to aim to return to some previous condition which we imagine as having been capable of preservation in perpetuity.”

[Episode 1: Markets and the Ontology of Possession]

Speculation, risk, precarity, globalised trade — these are not only the forces that shape the art market, they are encoded into artworks themselves. The very values we praise in contemporary art — transience, ephemerality, dispersion —mirror the flows of financial capital.

T.S Eliot feared and despised unrestrained capitalism. Capitalism, he wrote, “is imperfectly adapted to every purpose except that of making money; and even for money-making it does not work very well, for its rewards are neither conducive to social justice nor even proportioned to intellectual ability.”

Artworks are said to circulate, to escape ownership, to exist in a radical horizontal field. Each gesture of dispersal deepens the logic of possession. The market translates immaterial value back into capital. The more complex the circulation, the higher the price.

Possession here is not simple. Even when artworks pass through countless hands, a trace of authorship remains — a psychic residue of ownership. This contradiction is profitable. The more a work seems to resist ‘possession’, the more valuable it becomes.

This is what we might call an aesthetic of possession —art that symptomises its own desire to be owned. ‘Form and its content. Content says for commons, form says for market. Possession as indicator in defining subjects, possession constructs agency of subject, building relations to external world and other subjects.

Chris Evans, Subscription to Morning Star, 2014

[Episode 2: Politics of, or, as Destruction]

When Paul Kelleher decapitated the marble Guildhall statue of Margaret Thatcher in 2001, he described his act as “artistic expression and my right to interact with this broken world.” The statue had been commissioned in 1998 from sculptor Neil Simmons by the Speaker’s Advisory Committee on Works of Art, funded by an anonymous donor.

Kelleher’s gesture echoes Bruno Latour’s writing on iconoclasm — destruction not as rational critique but as a form of inarticulate expression. A visual register of anger. Kelleher’s act literalised the fantasy of liberation through destruction —art as violent unmaking of the image of power.

But the paradox is immediate. The destroyed statue became more charged than the intact one. The photograph of its beheading entered circulation as a new image-object —a radical act reabsorbed as spectacle.

In T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, he writes:

“In my beginning is my end.

In succession

Houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended…”

Destruction folds back into continuity. The radical gesture repeats the structure it opposes. The broken head of Thatcher becomes another commodity, another story of possession.

[Episode 3: In-between Social Necessity and Asset Value]

“All artists are alike. They dream of doing something that’s more social, more collaborative, and more real than art.”

—Dan Graham

This tension is not new. Art has long been knotted between social care and privatisation — between its Keynesian role as public good and its neoliberal status as asset class.

From the welfare-state model of cultural parity to the fully financialised art economy, we live within a contradiction —art as social necessity and art as speculative object.

The ‘artworld’ continues to celebrate “autonomy” — freedom of expression, artistic independence — but that autonomy is increasingly conditional. As Kester notes, this is an ontic privatisation —a freedom sustained by inequality. The artist’s freedom depends on structures that restrict it for others. If art is a space of unregulated freedom within an unequally regulated society, we must ask —whose freedom is this?

Muriel Rukeyser writes in “The Speed of Darkness”:

“The world is made of stories, not atoms.

The universe is not made of money,

but of the shapes we make from our desire to change it.”

In the context of contemporary art, her words strike with renewed force. The story of freedom, like the story of the market, is a story about possession — who owns the means of imagining.

[Episode 4: The Wiring Diagram — Systems and Repeatability]

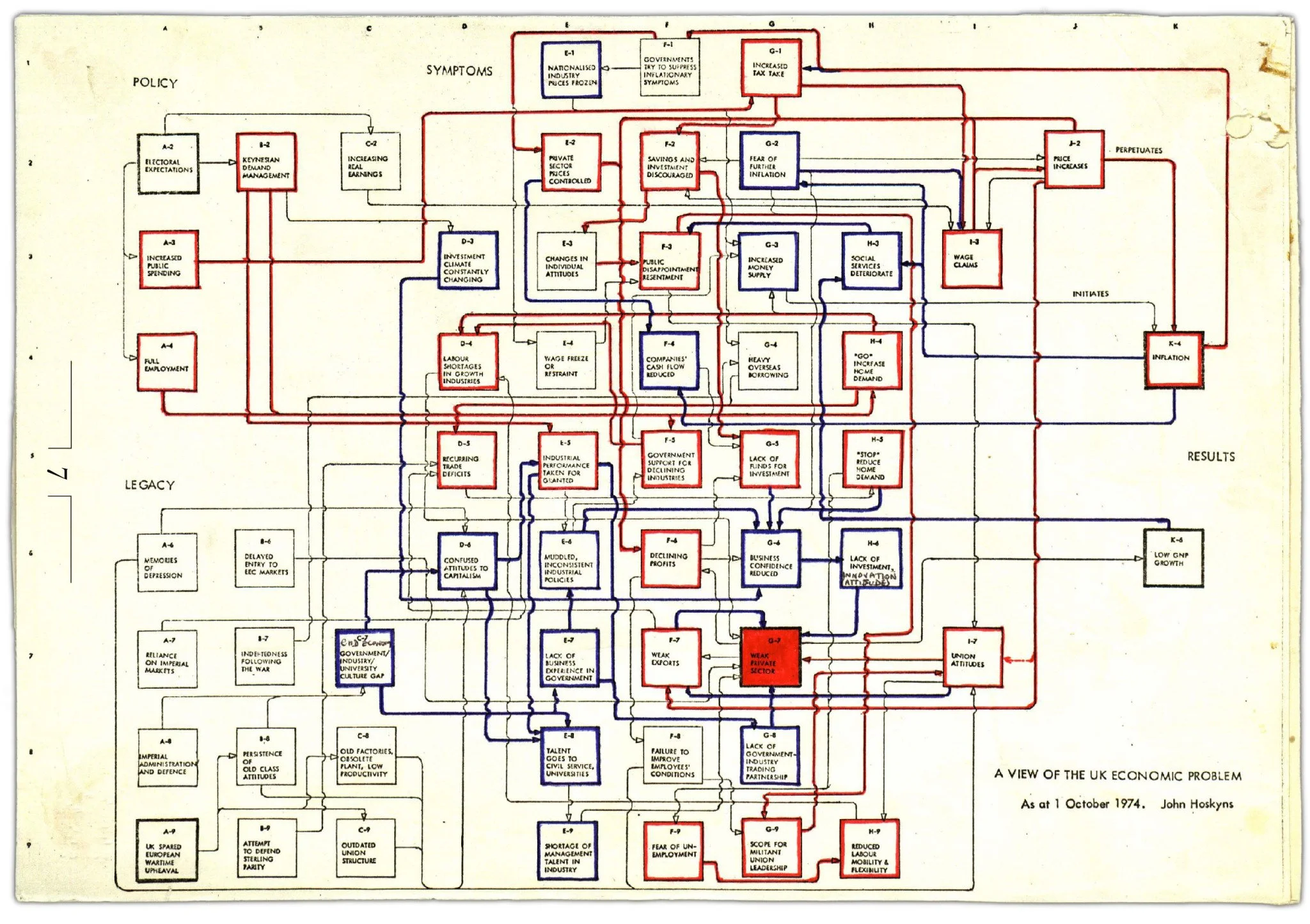

In 1974, John Hoskyns shared his visual thinking that diagrammed the factors and protagonists in The Wiring Diagram — a visual model of Britain’s failing mid-seventies economy. Jumble of pathways, chaotic routes, plotted circuits and links, a tangle of feedback loops.

The diagram’s logic is mechanical. Each circuit implies predictability —a system that can be reset, rerun, controlled. The various positions have a sense of reversibility, an air of linear-causal rationale. A set of relations that can be re-run with much the same result each time - or with little leeway for difference of outcome, for detour and digression. It lends a stamp of reliability, consistency and coherence as would be expected of a considered socio-economic statement.

Margaret Thatcher will later use Hoskyns’s diagram to rationalise her “long march to the free market economy.” The promise was systemic reform —change everything, all at once.

The Wiring Diagram is at odds with how we might understand repetition in art practice and research where such degree of ‘exact repeatability’ is not only unlikely but undesirable. Each rerun would spawn unique, one off variants – where repetition amounts to unpredictable generation of divergence.

Repetition, in art, never produces the same result. Each reenactment spawns difference. To repeat is not to restore but to deviate. Repetition keeps the wound (of the past) open — a space for thinking difference within sameness.

[Episode 5: Reenactment, Retrieval, and the Radical Past]

Our moment is full of reenactments. Political protests restage earlier revolutions. Artists restage earlier works. Histories are rewritten, refilmed, reframed.

This can look like exhaustion — art turning inward, recycling its past. But reenactment can also be a strategy of retrieval, what Walter Benjamin called “a halt on history” — a pause that allows fragments of the past to flash into the present.

Adorno warned that “the only image of the future is the present, seen as fragment.” The future, he said, is premature. What we inherit are shards.

To work with fragments is not nostalgia but survival. As you write, radicalism itself becomes “a survival strategy of waning practice.” Modernism and commodity culture were born together, and they decay together.

Benjamin’s angel of history looks backward, blown forward by the storm we call progress. We, too, are caught between movement and ruin — between the radical and the conservative gesture, both turning on the same axis.

Power sharing in Tahir Square, Egypt, 2011

[Episode 6: Circulation]

Contemporary artists, faced with this impasse, have developed new forms of reframing, rearranging found images and objects, giving them new relations in space. Or, recapturing — documenting time, collecting fragments, building collections. Or, reiterating principally through performing and re-staging past events to test their persistence. Or, researching — excavating hidden structures of place and economy, producing speculative documents.

These practices share one trait. They manipulate performance rather than inventing new content. Their power lies in formatting — in how images connect to the social currencies of capital and politics.

As David Jozelit quotes:

“Art links social elites, sophisticated philosophy, practical skill, mass publics, financial speculation, and national identity. No other discipline combines these in one format. This formatting is its unique power.”

Art’s task is not to negate that power but to understand it — to make visible how possession, circulation, and belief operate together.

[Episode 7: Radical Conservatism Reconsidered]

Perhaps we have never been modern. Bruno Latour calls this a “nonmodern life” — cyborgian, networked, entangled. We follow both humans and nonhumans across circuits of power, tracing how boundaries are made and remade.

Within this view, the radical and the conservative are not opposites but interdependent movements. To conserve becomes to hold open the conditions of critique —to be radical is to reconfigure what is already there.

As Eliot put it:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

To know the place for the first time — that might be the project of radical conservatism?

[Epilogue]

Art cannot go it alone. It never could. Perhaps the avant-garde did not collapse from within but was politically rolled back by the forces around it.

Still, art remains a site where contradiction is visible — where the possessive logic of capital and the promise of the commons uneasily coexist .

The task is not purity but persistence —to sustain this contradiction long enough for new forms to be figured. Radical conservatism, then, is not an oxymoron, but, at best, a method — a way of thinking art’s desire to hold and to change, to keep and to break.

Or, is it the ‘glimpsed alternative’, the ‘redress of poetry’ —not to escape from the world, but a means of bearing its weight.

Castlefield Gallery is pleased to present Radical Conservatism, curated by Pil and Galia Kollectiv for its Art & Society strand of exhibitions.

The exhibition includes works by:

Chris Evans (London); IRWIN group, founded in Ljubljana (Slovenia); Joseph Lewis (London); Patrick Moran editor of the metal fanzine Buried (London); Oscar Nemon (b. 1906 Osijek, Croatia d. 1985 Oxford, UK); Pil and Galia Kollectiv (London) and Public Movement (Israel).

Pil and Galia Kollectiv,

Still from Performative Construction of a Future Monument… 2009

Symposium: Radical Conservatism

Professor Alun Rowlands is a curator and writer, lecturer working at the University of Reading. He co-curated The Dark Monarch at Tate St Ives and Towner Eastbourne in 2010. He has a particular interest in the ways in which artists and writers create social interstices through itinerant self organisation, samizdat publishing and collaboration; alongside the history of alternative spaces and notions of the artists’ colony.

Chris Evans’ work often evolves through conversation with people from diverse walks of life. Sculptures, letters, drawings, film scripts and unwieldy social situations created as a result of this, are indexes of a larger structure through which Evans deliberately confuses the roles of artist and patron, genius and muse. Evans has exhibited widely and is currently showing work in ‘The Narrators’, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, curated from the British Arts Council collection. Recent exhibitions include solo presentations at Juliette Jongma, Amsterdam (“CLODS, Diplomatic Letters”, 2012); Luettgenmeijer, Berlin (“Goofy Audit”, 2011) and group exhibitions at Marianne Boesky, New York (‘Specific Collisions II’, 2013), De Appel, Amsterdam (‘Bourgeois Leftovers’, 2013); Witte de With, Rotterdam (‘Surplus Authors’, 2012) and performances at Wysing Arts Centre, Cambridge, UK & The Northern Charter, Newcastle, UK (‘Errors Hit Orient’, 2013). In 2014 Evans will participate in the Liverpool Biennial.

Pil and Galia Kollectiv are London based artists, writers and curators working in collaboration. Their work addresses the legacy of modernism and explores avant-garde discourses of the twentieth century and the way they operate in the context of a changing landscape of creative work and instrumentalised leisure.

Robert Garnett is a writer and art-ctitic based in London. He has written for a wide variety of Uk and international art publications, including regular contributions to Art Monthly and Frieze. Robert is co-editor with Andrew Hunt of the critically acclaimed anthology, Gest: Laboratory of Synthesis #1, (London: Bookworks, 2008), initiated by a series of events and discussions during the exhibition ‘Gest’ — at the Stanley Picker Gallery, Kingston University. Robert’s other recent work explores the concept of humour in the writing of Giles Deleuze.

T.S Eliot, 'Burnt Norton, (No. 1 of Four Quartets) 1936

The Wiring Diagram. 01.10.1974. by John Hoskyns. Reproduction from ‘Just in Time’ (Aurum Press. 2000)