Footnotes for the Smiles are not Smiles

ART OF THE EIGHTIES AND SEVENTIES, Michael Stevenson, Revolver 2007

96 pp. ISBN 9783865881984

CONTENTS:

»Forward. Vorwort« Susanne Titz

»Meeting Johannes Cladders & Hans Hollein« conversation with Susanne Titz & Chantal Jacobi

»A Story. Eine Geschichte«

»Notes. Ammerkungen« Alun Rowlands

»Essay« David Craig

DESIGN:

Christoph Keller

DESCRIPTION:

317mm x 250mm, 128 pages, black and white with colour section, hard covered with dust jacket, (English/German)

PUBLISHER:

Revolver – Archiv für aktuelle Kunst Frankfurt

Michael Stevenson, The Smiles are not Smiles, 2005, Städtisches Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach

For further documentation, see:

https://michaelstevenson.info/

Tehran, late October 1978, a new commercial gallery is about to open its doors to an expectant public; their patience, however, dwindles by the hour. Outside is confusion. Across the city suitcases are being packed, decisions are being made and different lives imagined.

Tony Shafrazi, gallerist, artist, and courtier to the Peacock Throne, launched his first space in Tehran amidst chaos and revolution. Awaiting the public was a stacked wall of freshly gold-leafed bricks by Armenian-born artist, Zadik Zadikian. Serene, delicate, momentary, it's golden flakes shedding with every passing breath of air. Outside, rioting, later looting.

The bricks disappear—the gallery shuts—the airport is overrun

Footnotes for the Smiles are not Smiles, originally presented as a lightbox accompanying Michael Stevenson’s exhibition ‘The Smiles are not Smiles’, Vilma Gold Gallery, London. Notes was adapted and expanded for the publication ART OF THE EIGHTIES AND SEVENTIES, Revolver 2007.

The text navigates art, revolution, and authority in late 1970s Tehran, with Tony Shafrazi’s gallery serving as an inadvertent witness to history during a time of civil unrest and institutional transformation. Drawing on archival anecdotes, economic data, and critical theory, it traces the complex relationship between art and power, highlighting the spectacle and eventual collapse of the Shah’s regime, the looting of Tehran’s galleries, and the shifting fate of Western art collections after the revolution. Engaging stories — including Shafrazi’s notorious Guernica incident and his role as advisor to Empress Farah — reveals the contradictions within museum institutions, exposing how radical artistic impulses are negated within these frameworks. Through firsthand accounts, literary references, and nuanced juxtapositions of art, revolution, and memory, the text critically explores the fragility of modernist ambitions amid profound societal upheaval and ideological change. The footnotes to an exhibition emphasise how museums, collections, and galleries reflect and shape authority, taste, and resistance, showing how economic instability, revolutionary politics, and ideological conflicts transform artworks and spaces from symbols of power into cultural hostages or emblems of loss.

Notes

i October 1971. The Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi threw a party. Held within the ruins of Persepolis it celebrated 2 500th anniversary of the Persian Empire, the Shah’s thirtieth anniversary on the throne and the tenth anniversary of the White Revolution his modern reform programme. Those invited represented the panoply of power. An encampment of tents was constructed on the dry plateau. At the centre of Parisian decorator Jansen’s sumptuous tent city was the Shah and Empress’ apartment draped in ruby velvet and gilded with gold. Scores of smaller tents fanned away from the centre complete with two bedrooms, two marble bathrooms and a chic sitting room. Top hairdressers flew in from Paris. Elizabeth Arden created a new makeup, to be given in kits to the guests, named after the Empress ‘Farah’. Robert Havilland produced a cup and saucer service to be used once by arriving guests. Lanvin created new uniforms for the court stitched with over a mile of gold thread. The food and wines were French. After the banquet there was a son et lumiere spectacle and fireworks display. The whole spectacle-displayed wealth accrued from the price rises in oil. At Persepolis, the Shah moulded Persian history to his own desire. The cost of his revisionism was anything up to $300 million. But the real cost to the Peacock Throne would manifest itself in revolution.

ii 'We couldn't move; we were all stunned,' said Gregory Losapio, 16 years old, who was in the museum with his Scarsdale High School class. ‘Stunned visitors looked on helplessly in the third floor gallery where Picasso’s Guernica hangs. A man drew a can of spray paint from his pocket and scrawled three words ‘Kill Lies All’ in foot-high letters across the masterpiece. 'A man started to move toward the guy when he turned around, cursed and said: I'm an artist and I want to tell the truth' the student said. The vandal was identified as Tony Shafrazi, an Iranian artist. Mr. Shafrazi was taken to the West 54th Street station house and was charged.

- Source: The New York Times, March 1, 1974

iii Housed at MOMA throughout the 1960’s Guernica was incorporated into the protest rhetoric of the Vietnam War. Numerous posters appropriated the painting as an image. Anti war groups contacted Picasso and requested he withdraw the painting from the museum. The Artists Workers Coalition sought an Art Strike against war, repression and racism.

iv 'I wanted to bring the art absolutely up to date, to retrieve it from art history and give it life. Maybe that's why the Guernica action remains so difficult to deal with. I wanted to dwell within the act of the painting's creation, get involved with the making of the work, put my hand within it and by that act encourage the individual viewer to challenge it, deal with it and thus see it in its dynamic raw state as it was being made, not as a piece of history.'

(Tony Shafrazi)

- Source: Art in America, December 1980

v Museums have been depicted as asylums. The works of art they housed appeared to be going through some kind of aesthetic convalescence. Separated from society they were politically lobotomised, inanimate invalids ready for consumption. (Smithson). Institutional practices, the ruling force of political and economic factors, reveal the museum as subject to the shifting associations of authority. It exerts and reflects specific contradictions in society. The museum's position as the most authoritative art institution allows it to govern the construction of the present and projection of the future. Contemporary art's critique of the museum, even if reluctantly, still 'belongs' to the museum. The iconoclastic violence of the avant-garde is neutralised by the art institution. Radical transgression is no longer a break with the museum, but what we expect to find in this modern house of worship. These broadside attacks nevertheless recognised that the museum is an arena in which power is secured and acknowledged.

vi The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art opened its doors in October 1977. The building, a modernist vision by architect Kamran Diba, is a cross between New York’s Guggenheim Museum for its entrance and the Saint-Paul-de-Vence Maeght Foundation for its exhibition rooms. The Empress Farah Pahlavi founded the museum with money from the country’s immense oil reserves. The opening was a great occasion and fanfare with a guest list including Henry Kissinger and Nelson Rockefeller. The collection contained major masterpieces of western art from Monet and Gauguin to Warhol and Lichtenstein.

vii The collection provides a snapshot of a period in the history of taste. This was a time in the 1970s when the extremely wealthy undertook the creation of a museum from scratch. The artworks recall the circumstances under which they were acquired. All art galleries and dealers remember the museum’s patronage as a godsend. While Western economies were hit with the 1974 oil crisis, the museum saved many galleries from bankruptcy. Tony Shafrazi became Empress Farah Pahlavi’s art advisor having established himself as gallerist ironically representing ‘graffiti’ artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring.

viii By the late 1970s the New York art scene was in upheaval. Both stylistically and economically there were different schemes of evaluation tied to competing and contradictory philosophies. Thisix emergence carried socio-political ramifications that were divisive. Economically, international markets were sought to infuse the slumping art market. In this climate art galleries were having difficulties staying afloat. The average lifespan of a gallery was only one year. Even though there was a net increase in the total number of art galleries over the decade, the fortunes of individual galleries were very precarious. The real innovations within this period happened less in the studios than in the spaces that displayed them. The promotion of young artists, in cheap recession-hit storefronts, allowed first time gallerists, with no qualifications other than enthusiasm and the ability to host a good party, to define a new modernism.

ix ‘Pimping was a highly developed art form in Tehran. Business and sex were inextricably intertwined. At the height of the Shah’s excesses he insisted on making love to a minister’s daughter in a helicopter as it hovered over the city of Isfahan.’

- William Shawcross The Shah’s Last Ride: The Fate of an Ally Simon & Schuster (1988)

x Gold trades at an average of 16-17 barrels of Oil per ounce of Gold. Gold and oil traditionally have had a 15-to-1 relationship, only slipping out of congruence for short periods of time. When the gold/dollar relationship is anchored, the oil/dollar relationship remains stable as well. When the dollar/gold relationship is malfunctioning, as it was in the late 1970s, capital is wasted as producers try to protect themselves from the damaging impact of inflations and deflations. In 1977 when inflation began to pick up steam it reached 9% by 1978. Gold followed by breaking its previous high of $200. When Inflation hit 10% in 1979, Gold really took off skyrocketing to $500. Excitement kicked in and a Gold rush mania launched the yellow metal to its all time high of $850 in 1980.

Source: US Treasury

xi 1974. Zadik Zadikian, flees Armenia to New York City. He befriends Richard Serra and assists in the production of his large-scale black oil wall drawings. The first of these is named- ‘Zadikian’. The cultural-economic life of New York has a profound effect on Zadikian. In 1976 he covers his entire home and studio, 10 000 square feet of walls, floor and ceiling with industrial gold, by pounding and gilding so as to transform it into a ‘singularly radiant vision.’

xii Modernity in an Iranian context was a complex field of negotiation and accommodation. In the years leading up to the revolution, religious and secular consciousness coexisted. Artists and their galleries were lured by the Shah’s vision of Iranian modernism to open galleries and publish journals of contemporary art in Tehran.

xiii Former director of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Kamran Diba, evocatively referred to this trend as Spiritual Pop Art: "There is a parallel between Saqqak-khaneh [Iranian folk art] and Pop Art, if we simplify Pop Art as an art movement which looks at the symbols and tools of a mass consumer society as a relevant and influencing cultural force. Saqqak-khaneh artists looked at the inner beliefs and popular symbols, that were part of the religion and culture of Iran and are consumed in the same way as industrial products in the West."

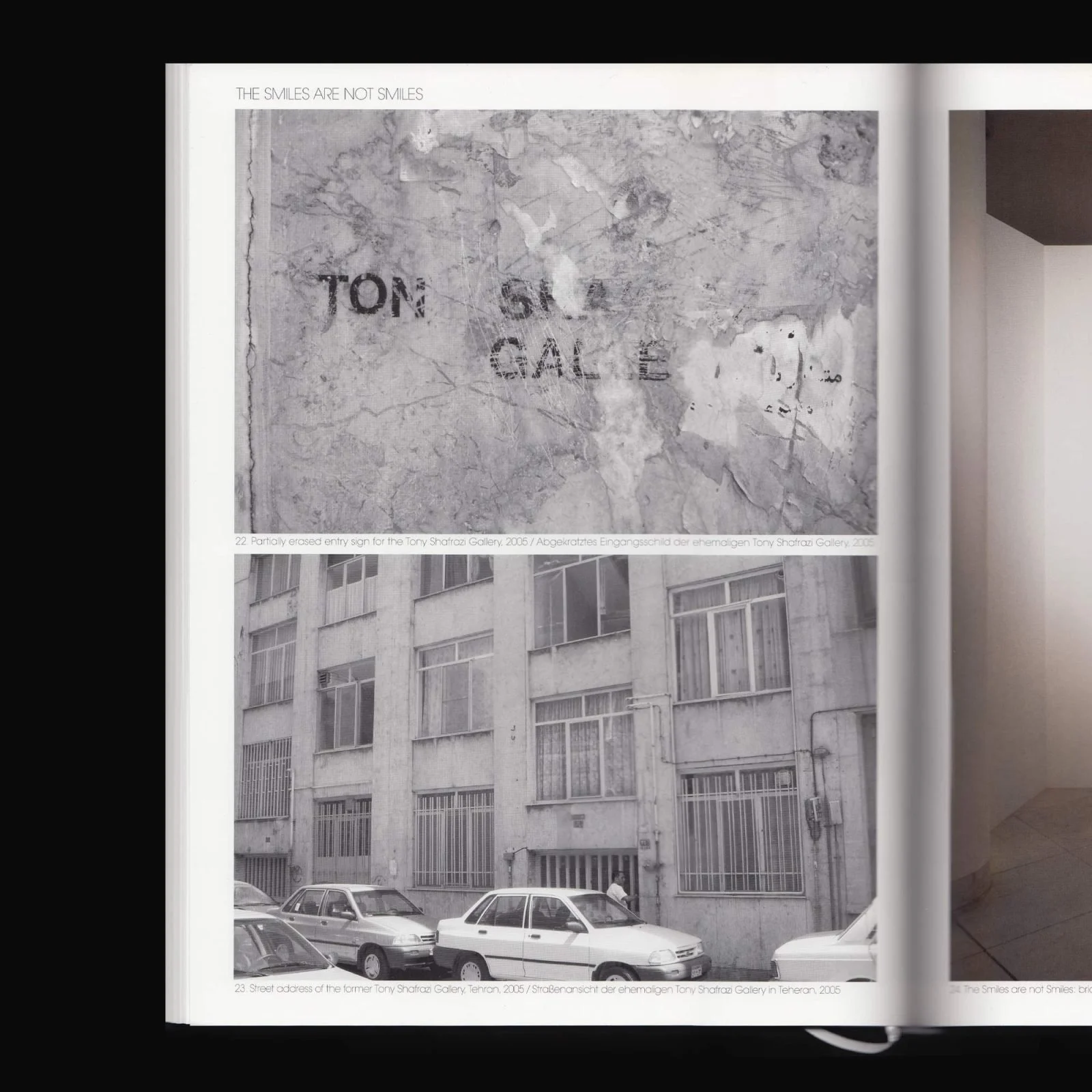

October 31. 1978. Takhttavoos. Koohe Noor St. 3 Rd St. No. 26 Tehran. Tony Shafrazi presents ‘Gold Bricks’ by Zadik Zadikian. The inaugural exhibition of Shafrazi’s new Tehran gallery opened with a backdrop of civil unrest and sporadic violence. Waves of rioting were a prelude to revolution. The gallery was looted. All that remained was the invitation card that unwittingly announced the date of the revolution. The exhibition was an inadvertent witness to historical change. The gallery closed.

xiv In the face of growing religious fervour and mounting opposition to excessive Westernisation, the Shah and Empress announcd their departure from Iran on an ‘extended vacation’ in Egypt. The downfall of the Shah and the ascendancy of Khomeini signalled a critical threat to American interests and cultural imperialism in the region. With the deposition of the royal family the collection at the Museum of Contemporary Art was seized and consigned to storage. Western art historians referred to the invisible collection as ‘The Treasure’. The artworks were the cultural hostages of the revolutionary moment. The revolution swept aside the various forms of modernity through the imposition of an Islamic state. Pictures of the mullahs began to appear on the walls and in the windows of shops and government offices. Some posters contained echoes of the rhetorical geometry of the Russian Constructivists depicting red arrows smashing black pedestals topped with symbols of the Shah and the United States. Others brought to mind Pop art. Ayatollah Khomeini’s overexposed black and white face appears against a Warholian backdrop. The posters and revolutionary paraphernalia demonstrate that a number of currents intermingled and coexisted with Islamic zeal.

xv ‘Islam asserts that on the unappealable Day of Judgement every perpetrator of the image of a living creature will be raised from the dead with his works, and he will be commanded to bring them to life, and he will fail and be cast out with them into the fires of punishment.’

- Jorges Luis Borges, Dreamtigers

xvi ‘Art, especially pieces with themes that were less than Islamically correct, were displayed in private showings by invitation only… Otherwise, the theocrats were relentless in forcing art to conform to Islamic modesty. After the revolution, the government even issued an ultimatum to the Museum of Contemporary Art about a large bronze statue of a female at the entrance: Either take it down or comply. The statue was preserved by adding a crude fibreglass hejab to her hair and legs. Other art wasn’t so fortunate. In an Iranian art-book the ballerinas in Edgar Degas’ famous Dancers Practicing at the Barre were airbrushed out completely, leaving an empty room and practice bar. The tutus didn’t meet the standards of the hejab.’

- Robin Wright The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and Transformation in Iran. (Vintage). 2001

xvii Among the challenges to capitalist Modernism complacency has been an awareness that concepts which we consider unequivocally good- among them modernity, democracy and individual liberty- are often considered far more problematic in other parts of the world. ‘Freedom’ appears to many in the non-Western world as a code word for the forced imposition of a fraudulent Modernism. How salutary is modernity if it is accompanied by the erasure of cultural traditions? Perhaps the task is to seek new ways to participate in the global economy that does not involve the torsions of free-market capitalism. The attempt is to examine the adaptation of modernism in a country that has experienced revolution, fundamentalism and period of reformism, to provide an account of the theoretical and ideological conflicts between art and the forces of revolution.

Published on the occasion of Michael Stevenson’s exhibition, ART OF THE EIGHTIES AND SEVENTIES at the Städtisches Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach.

Referencing both Hans Hollein’s postmodern design of the museum and the 1978 Tehran gallery exhibition ‘Gold Bricks’, on short display during the outbreak of the revolution–a sculptural work by Armenian artist Zadik Zadikian which disappeared without a trace through looting.

This exhibition was the first and only show of a gallery that Toni Shafrazi, who later became successful in New York, opened in Tehran in 1978.

Stevenson reconstructs the situation of the exhibition Gold Bricks in Tehran, which was briefly shown in 1978 during the outbreak of the Revolution—a sculptural work by the Armenian artist Zadik Zadikian that vanished without trace due to looting. This exhibition was the first and only presentation by a gallery that the later New York–based gallerist Toni Shafrazi had opened in Tehran in 1978.

As the central project of his exhibition, Stevenson realized a large-scale installation in the main exhibition hall under the title ART OF THE EIGHTIES AND THE SEVENTIES. This served as an architectural intervention within the Museum Abteiberg. At a 1:1 scale, the top floor of the museum tower was reconstructed. It was staged as a walk-in space whose form matches that of the original tower, but which appears as though in the state of an archaeological site, a ruin. Rice fields and debris cover the building, leaving behind only rough fragments of the original walls.

Extensive research plays a key role in Stevenson’s works, often uncovering hidden connections within the art world. A second installation at the Museum Abteiberg, The Smiles are not Smiles (first presented at the Vilma Gold Gallery, London), also deals with the 1970s and takes shape within the museum’s collection display as a space dense with relics.

Michael Stevenson, ART OF THE EIGHTIES AND SEVENTIS, 2005, Städtisches Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach