Fear it, do it anyway

FEAR IT DO IT ANYWAY

Vilma Gold Gallery, London

13 January - 11 February 2001

curated by Alun Rowlands &

Mark Dickenson

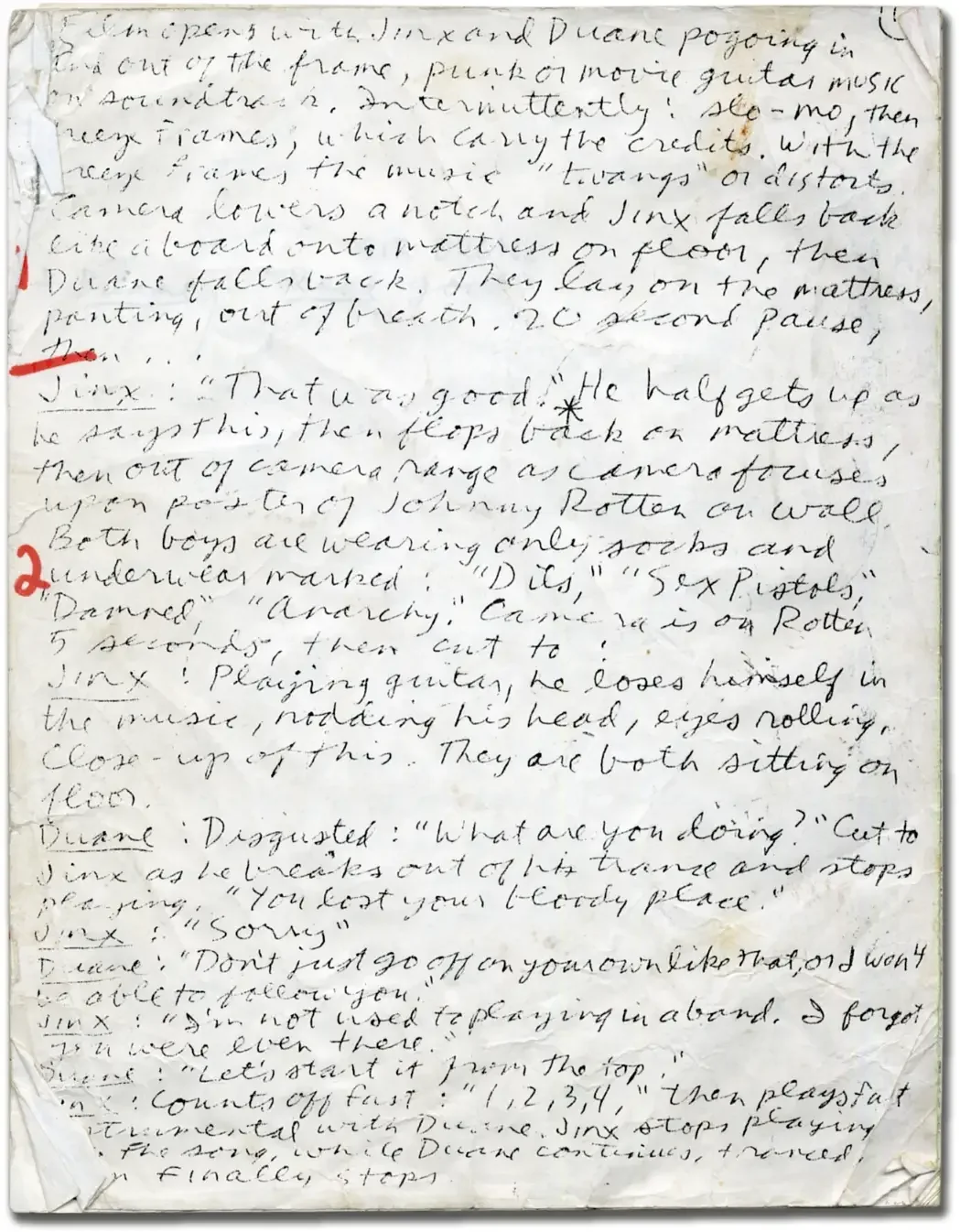

Raymond Pettibon, director. Sir Drone. Featuring Mike Kelley. 1989. Film.

Sir Drone is half myth, half deadpan joke, filmed in scrappy black and white and full of missed cues. Mike Kelley and Mike Watt (Destroy All Monsters) play losers on the brink of punk, rehearsing failure as destiny. Dialogue loops like bad lyrics, scenes dissolve into talk about starting a band, never quite playing a note. The film drifts through garages, bedrooms, and empty suburban lots, where rock’n’roll exists only as promise, or maybe a curse. Pettibon’s camera treats speech like noise — flat, repetitive, slightly off-tempo —while Kelley’s delivery turns frustration into performance. It’s a portrait of ambition stripped bare, dreaming through borrowed riffs, waiting for recognition that never comes. The humour is dry but cruel, the rhythm broken. Every cut reads like a failed edit, every pause a question about what it meant to be a fan when the music stopped. Sir Drone is punk’s ghost story—funny, bleak, and too familiar to dismiss.

Sir Drone, 1989, film stills.

Fear it, Do it Anyway brings together artists that use Rock as a platform to initiate work that dissects the roots of culture and ideology. Rock is a trigger. It evokes ‘a moment’ —an encounter in a wider socio-historical field.

Dan Graham’s Rock My Religion sits here as a keystone. The ecstatic labour of Shaker worship morphs into the frenzy of punk shows. His argument is blunt —the rock ethos of ‘fun’ was born from deferred pleasure in the shadow of annihilation. Teenagers faced the A-bomb. Sex was cut loose from the duty of reproduction. Rock mocked parental faith in sublimation, marriage, and work as the necessary path. Rock heroes were sinners without shame. Bands became proto-communes —families without nuclei.

Raymond Pettibon’s Sir Drone picks up this spirit—part narrative, part myth. Early punk retold as scrappy fable: two guys in search of the band, drifting through suburbia, chasing the hum of guitars. Pettibon’s pen draws rhythm. Dialogue fragments work like song lyrics stripped of melody. His lines are both caricature and scripture, fixing rock culture somewhere between street-level anecdote and sacred text.

Evan Holloway’s Drum Box takes music out of myth and puts it into tactile absurdity. A sculpture that is also an instrument, a kit you inhabit. The work dials down virtuosity; it amplifies the physical presence of sound-making, the shared headspace of noise and bodies. Holloway edges rock into sculptural play, rebuilding the stage into a communal object.

Mark Titchner’s early text works cut rock into slogans. Language is weaponised into refrains—commands, pleas, and looped mantras that could be album covers or protest signs. His phrases riff on band aesthetics and political rhetoric alike, collapsing the gap between the gig poster and the declaration of faith. In these works rock language is stripped down like a raw drumbeat: no harmony, just insistence.

George Shaw’s drawings haunt the edges of this conversation. British suburbia rendered through lacquers and biro. References to music—often fringe or forgotten tracks—create collisions between teenage interiors and public mythologies. In Shaw’s hands, the playlist is a time machine, sifting memories of cheap stereo hum into the quiet violence of nostalgia.

The exhibition builds itself without theme, but by replication of the band-as-family model. Loose ties. Non-linear kinship. Unstable roles. Graham’s teenagers pivot through Pettibon’s myth, Holloway’s stage-object, Titchner’s slogans, Shaw’s late-night soundtrack. Each artist works from familiarity—the record heard too young, the lyric misheard, the poster glimpsed.

Connections shift from logical mapping to intuitive jumps. Drift into fiction, into dreamt riffs or invented band names. Memory itself becomes performance, sometimes acute, sometimes muffled. A perfect recall of a bassline or the faint smell of a club coatroom. The works move between time frames, past into present, gig into archive, object into echo. Their relationship to rock is neither celebratory nor cynical—it is an ongoing method. Noise becomes an investigative tool. Lyrics become manifestos. A set-list becomes a structure for thinking.

Evan Holloway, Drum Box 1997, 7-inch vinyl record, Cover 18.2 × 18.4 cm, Edition 300

'In 1997 I made a sculpture called the Drum Box that was a large soundboard covered cube about 2.5 meters high. Inside was a much smaller chamber just large enough to hold a drummer and a drum kit. All the space between the inside and the outside was elaborately soundproofed and the chamber sealed with a series of soundproofed doors. Air had to be pumped in to prevent suffocation. Anyway, if someone was inside the box playing very loudly it would sound like they were about 3 blocks away. You would know that there was someone in there playing but the sound you heard wouldn't reckon the distance correctly. Inside the box was another experience, any competent drummer could enter the box and play but he or she had to agree to play for a very extended time, at least 2 hours straight, and to try to use the drumming as a way to get high.'

Fear it, Do it Anyway, Exhibition image, Vilma Gold Gallery, 2001