Arthur R Rose

Arthur R. Rose, Tanner Place, 54-58 Tanner Street, Bermondsey, London SE1, 1997 - 2000

Doris Kroth, Rosicrucians, sound, 1998

“Arthur R. Rose was not a group so much as a set of excuses to initiate exhibitions, publications and events. Artists, joined loosely, moving through work, through talk, through the debris of art and its demands. Begun in 1997, in Bermondsey, it first held a space — then let it go. The projects that followed tried to unlearn old habits, to speak more quietly, to leave room. Objects appeared, were considered, disappeared. The need to supply, to produce—set aside, or tried to be. Instead, they lingered, tested what is possible. Effort without certainty. No fixed routine. What remained was the attempt — to find a way of working in the gaps. To show without showing, to act without the grip of purpose.

Arthur R. Rose moved and used what passes for a system — the informal, the borrowed, the provisional — to circulate its own sense of things. No fixed address. No promise of coherence. The artist’s routine task — to produce for display, for exchange — is set aside. In its place, a slower motion, an uncertain continuity. Each project had its own weather. A sense of time. They carried a faint humour, a kind of absence worn thin. The gallery, if it appeared at all, was surface only — one more imaginary ground. The rest was movement, waiting, contact, loss. In 2000, the room closed. The work continued, not closing the question.”

Elizabeth Price, Hearse attending…. (A Gallery Necrology), 1999 —photograph that documents the visit of a funeral hearse to a contemporary art venue —here, Arthur R. Rose, London. In each case the venue commissions the production of the photograph, which is exhibited within the chosen gallery.

Andrew Grassie, Arthur R. Rose Gallery, 1999, (21.6 x 26.7 cm.)

Andrew Grassie’s meticulously detailed egg tempera paintings depict gallery spaces and exhibition rooms, sometimes painted before the exhibitions themselves have taken place. Grassie produced works such as “Arthur R. Rose Gallery, 1999,” in which he painted the gallery space as it appeared prior to the installation or opening of an exhibition, capturing the environment in a state of anticipation.

This work functions as a kind of ‘document,’ reflecting on exhibition time and visibility, and the role of painting as a record. Grassie’s series often present spaces “locked into time,” sometimes with signs of imminent change, waiting for installation, emphasizing the ‘in-between’ moment before art appears. The paintings duplicate and double the actual spaces, questioning illusion and the artifice of exhibitions.

Christopher Warmington, 1999

“In 1997, Elizabeth Price exhibited a ball of brown sticky tape. Several years and exhibitions later, it is now the size of a small boulder (its title) and still growing. In her current show is a trophy —an object celebrating nothing more than itself and the occasion of its display. Whether it's a ball of brown tape, a shiny cup or, as in the case of Dot, a list of perfunctory instructions, Price has a talent for realising the unpredictable potential of seemingly prosaic objects and situations--allowing them to take on a life of their own.

Every two months between April 1999 and 31 March 2000, Price wrote to 15 artists inviting them to take part in Dot, a project she was organising from her studio, which resulted in an exhibition, Snowballing. The participants were invited to make use of the facilities offered by Price's studio: the site, duration, postal address, telephone number,…”

Jansz, Elinor. "Snowballing: a project by Elizabeth Price." MAKE: The Magazine of Women's Art, no. 88, June-Aug. 2000, pp. 30+

Objects are simple, 1998. Exhibition view, Arthur R. Rose.

Elizabeth Price began with sculptures that had no finished state —an endlessly growing ball of brown packing tape, an increasingly damaged plinth that is left unprotected when transported between shows, and a trophy engraved with the name of each gallery that exhibits it. ‘Boulder…’ 1998 is a spherical sculpture made of wound packing tape. It is exhibited intermittently, but on each occasion it demonstrates an increase in size. An endless text of these exhibitions document the sculpture’s gradual expansion, as well as its passage through a series of transitory contexts and spaces. Her works unfold over indefinite or protracted periods of time, during which new material is episodically generated and disseminated, through exhibitions, events and publications. Cumulatively these episodes come to generate detailed archives narrating transitory, defunct and imaginary art institutions or organisations.

Karin Ruggaber, Set, 1999, Exhibition view.

Emerging from Ruggaber’s studio-based exploration of material and surfaces, ‘Set’ 1999, investigates principles of ordering, layering, and the spatial interplay of portable architectural elements. The work is characteristic of Ruggaber's approach —oscillating between the decorative and the utilitarian, engaging with the thresholds of aesthetics and reference. Through subtle variations in texture and the orchestration of materials, ‘Set’ resonates as both an object of experience and an inquiry into form and display within a gallery context. The work resists interpretation, operating from within the interior logic of art, presenting itself as a crystallisation of evolving sculptural and spatial narratives.

Pavel Büchler, Previous Correspondence, 2001, consists of hundreds of letters in which Büchler systematically replied to unsolicited postal advertising or correspondence. The project evolved in two phases. In the first, each sender was informed—via printed letterhead reproducing his typewritten text—that their name had been added to a list; in the second, the process was reversed, and senders were told their names had been removed. For this exhibition Büchler has redirected all his postal mail —circulars, divorce proceedings, utility bills, correspondence to Arthur R. Rose for the duration of the show.

Büchler’s project plays on bureaucratic mechanics, authorship, and delegated agency—the gallery effectively became custodian of ongoing correspondence whose opening or non‑opening affected the work’s meaning. The pile or archive of letters, visually modest but conceptually loaded, examined what happens when administrative communication becomes aesthetic material. The idea that the gallery might have to “act” on any opened item fits precisely Büchler’s logic of ‘making nothing happen’, a phrase he uses to describe the catalyst role of art rather than object production

Ian Whittlesea, ‘The light from Fiona Banner’s studio’, 1997, ink on paper, signed by the artist & Fiona Banner.

29.7 x 21 cm

’On Friday the 4th April 1997 at 2.15pm the level of ambient light in Fiona Banner’s studio was measured at 2800 lux. This work allows the owner or exhibitor of the work to recreate this level of light in a space of their chosing.

Ian Whittlesea, Statement Paintings, 1999 These text-based paintings document and extract statements from artists such as Walter De Maria, Sol Lewitt, Piet Mondrian, and Jackson Pollock, blending linguistic precision with painterly subtlety. The series is characterized by its restrained visual vocabulary and intellectual rigour, considering how art is embedded in specific positions and histories. Whittlesea’s work reflects on artistic exile, solitude, and the paradox of creative withdrawal as a necessary condition for engagement with the world, offering a conceptual meditation on the nature of artistic labor, memory, and presence.

Simon Morley's ‘book paintings’ represent a convergence of literary form and visual abstraction where the familiar structure of book covers is transformed into monochrome painted surfaces. These works explore the relationship between text and image through a visual language that evokes the materiality of books while rendering their titles and covers as textured, minimal planes. Morley’s paintings cite modernist traditions of monochrome abstraction but infuse them with layered cultural and narrative references, bridging the gap between reading and seeing. The interplay of form, typography, and surface encourages us to reconsider the boundaries between art and book design. His approach foregrounds processes of visual and intellectual engagement with memory, meaning, and the act of perception within the space of painted “covers.” This series signals Morley’s ongoing interrogation of cultural artifacts as sites of resonance beyond their functional uses.

David Blamey, Self Taught, 1999, 235 x 172 x 6 mm, 48 pages,

ISBN 0 949 00414 6

When David Blamey made an installation which comprised of a large vitrine displaying a collection of used rubber bands, he received a letter from an irate visitor complaining that his work was un-stimulating and less worth looking at than a forest. This book, that was published to coincide with another exhibition of the same material, tries to address the subjective nature of the evaluation of art. By jamming images of a forest, a tropical fish, a sunset, up against his own images of rubber bands, Blamey invites us to explore our own prejudices about the ambiguous hierarchical systems of value that are inherent in our society.

Pavel Büchler, Previous Correspondence, 2001

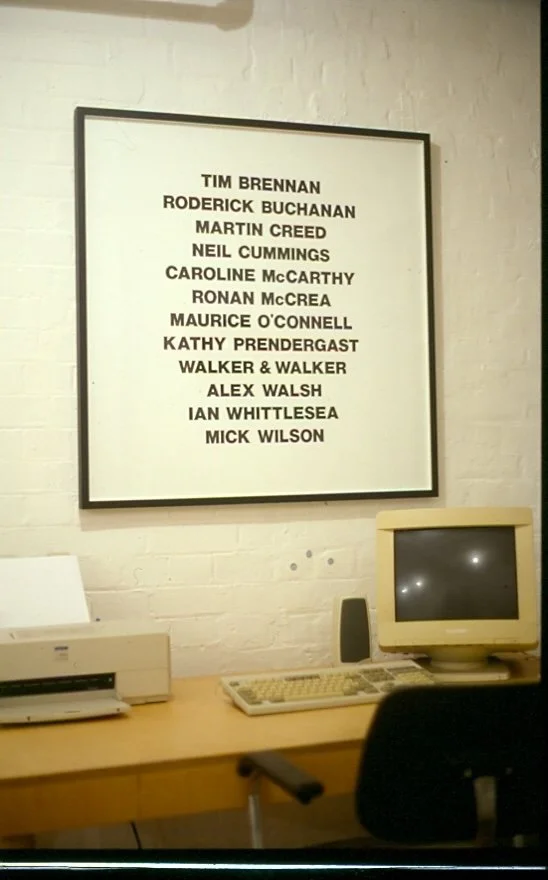

In Consistency, curated by Paul ONeill, 1999, September to October, 1999, Arthur R. Rose, London; and February to March 2000, Arthouse, Curved Street, Temple Bar, Dublin

Martin Creed,

Work No 79 Pack of Blue-Tac

Tim Brennan, The great things which are to be found among us the being of nothingness is the greatest

Mick Wilson, My Human’s Socratic Memorabilia (with Digressions) Amsterdam 1759

Neil Cummings / Marysia Lewandowska, Surrogate:an economy

Alex Walsh, Brian – August 1999

Grace Weir, Return

Mark Dickenson, 50 – 45.6%; 50 – 52.9%; 1 to 20

Walker & Walker, 153 cms

Andrew Grassie, Arthouse, Dublin, 2000

Caroline McCarthy, Souvenirs (Blue) and Golden Wonder

Roderick Buchanan, Brazil v Italy

David Blamey, Self Taught

Ronan McCrea, Untitled #1

“For this exhibition, curated by Paul ONeill, consistency has been projected as the purveyor of contents, ‘The Museum to the present physical state of Things’, (perhaps for Calvino, it would be ‘the Library’). Consistency reifies itself as a container of substance. Whilst Inconsistency is perceived as the collection; changing and fluctuating its contents, whilst dependent on ‘Consistency’ to define its state of existence or value.

‘Things that may be historically ‘Inconsistent’, but whose function and physical form remain ‘Consistent’ to their principle origin; eg. maps, plans, outline drawings, iconography, catalogues, souvenirs, information brochures, cartoons, diairies, calendars, generic consumer products, dictionaries, encyclopediae, etc. are examples.

To be part of ‘In Consistency’ is to consist of oneself; to contain self-reason. What consists of the collected object is self-evidential. Icons or things that provide meaning in spite of its ever fluctuating, historical or cultural value.

What consists of ‘the next Millennium’ when it is yet to take form. Are we to believe that it is ultimately about looking forward to a projected future-present where the past is but a thing called history? What are we left with when you cannot remember asking ‘how far back can you really remember?’ without a guilty feeling of nostalgia and self-doubt. Perhaps the constant attribute will be that of humour, when the only consistent response will be one of laughter and forgetting.”

Roderick Buchanan's Brazil vs Italy (1999) comprises a stereo trumpeting Brazil's national anthem 'Hino Nacional', followed by Italy's 'Fratelli d'Italia'. Brazil's anthem is the subject of much controversy: composed for Brazil's Independence, its lyrics refer to the 'dazzling rays of the sun of Liberty', while an alternative version sings praises to a Brazilian monarch. In contrast, 'Fratelli D'Italia' is an unambiguous call for Italian unity: 'Let's press like cohorts, we are ready to die'. Buchanan presents the anthems as orchestral versions for a brass band.

Caroline McCarthy, Souvenirs (Blue) and Golden Wonder, 1998, is a visual response to the contemporary language of travel and destination. Images from Travel brochures of resort destinations from around the globe are trimmed to reveal the heart of the image – the resort swimming pool. The cut-out pools are displayed in a row, beneath which a row of found crisps, each crisp an echo of the pool above. The elevation of the crisp, and its mimicking of the pools undermines the status of the destination image.

Martin Creed, Work No. 79, Some Blu-Tack kneaded, rolled into a ball, and depressed against a wall, 1993

Blu-Tac approx. 2.5 cm diameter

“As usual, you have to look hard to find Martin Creed’s work. There it is, a whole pack of Blu-Tack shaped into little circles and dotted around the walls to deliver a satisfying unity to an informal selection of works. If there is a link, it’s that these artists swap visual stimuli for introverted conceptualism. Creed’s piece is the most low-key, but Ian Whittlesea comes close with a text which lists the show’s participants, looks like a poster and is hung behind the desk to perpetuate the confusion. Roderick Buchanan’s Discman figures an abstracted, idealised version of an international football match which plays the national anthems of the two countries, one after another. Unpleasant post-match shenanigans—and the match itself—are airbrushed out. Neil Cummings continues his apparently endless look at disposable consumer goods in a video which soothingly cross-fades between brightly coloured baby’s dummies.

Everything is head-noddingly thoughtful. There are photographs of figures in the water, each approximately cut to the shape of the potato crisp mounted on the wall beneath it, a pair of ‘O’s drawings on paper and editioned as a thousand series, a toothbrush with its bristles replaced by human hair, a video of an empty passenger plane that questions notions of forward motion and stillness. A teasing sequence of lacunae, ‘In Cosistency’ offers a work out for the brain that won’t ruin your appetite.”

Review by Martin Herbert in TimeOut.

Richard Hogg, Arthur R. Rose, 2000