According to what?

According to what?

An exhibition of Bruce Nauman video works, Museum of Reading.

Another Pair

Paul Harrison and John Wood,

Beckett Centenary Commission,

Forbury Square, Reading.

Organised by Alun Rowlands and Professor Stephen Buckley, Department of Art, University of Reading.

Supported by Reading Museum Service, Artists in the City, Arts Council of England, Reading Borough Council, Stonemartin Corporate Centre and EAI, New York.

Samuel Beckett: Irish European a major biographical exhibition organised by University of Reading Beckett Collection.

Ground and Gait

Beckett and Nauman meet on the floor. Literally. Bodies fall, pace, and grind time into space. In Beckett, gravity shapes comedy and ruin at once. Think of the heap in Godot. In Nauman, falls, rolls, and prone bodies test a “zero condition.” Art does not elevate. It lays you out. It times the pressure of the ground.

Repetition is the motor. But not comfort. Molloy’s stones model an algorithm of compulsion. Nothing changes. Everything is counted. Nauman’s Slow Angle Walk (Beckett Walk) (1968) translates this logic into gait. Knees locked. Torso pitched forward. Camera rotated. A rule-bound loop that becomes ordeal. (Birnbaum 2000)

For both, space is made by doing. In Footfalls, identity needs the sound of the tread—“however faint they fall.” Place precipitates from pacing. Nauman’s studio walks and corridor pieces do the same. Stop moving and the world risks slipping away. Ground is limit and last resort. But it also shifts beneath the feet. (Connor 2000)

Each artist courts enclosure. Beckett’s mounds, cylinders, and square choreographies compress action into tight frames. Quad is percussion, paths, and attrition. Quad II pares further: black-and-white, silence, and the scrape of steps. Nauman’s tunnels and surveillance corridors echo this claustrophilia. Surfaces resist, define, and hold. Yet video splits presence. The “here-and-now” is cut by the “there-and-then.” A screen becomes a fickle ground. (Connor 2000; Lerm Hayes 2003)

Beckett pushes drama toward image, rhythm, and near-silence—“the obligation to express” despite the exhaustion of literature. Nauman pushes sculpture toward language, sound, and performance, often by subtracting the “visual.” Violin Tuned D.E.A.D. sounds a title before it plays a note you can parse. Concrete Tape Recorder Piece loops silence as an object. Each crosses genres to keep making work when a medium feels spent. (Lerm Hayes 2003)

Centers are suspect. Quad still circles a focal void. Nauman’s walk drifts the periphery, refusing anchor while insisting on repetition. His later clowns, dangling bodies, and screaming heads drive Beckett’s bleak humour into aggravated spectacle. Time does not pass; it presses. The viewer is conscripted as witness and counterweight. (Connor 2000; Lerm Hayes 2003; Birnbaum 2000)

Yet difference matters. Beckett’s late pieces achieve a ferocious economy. Nothing is redundant. A mouth. A square. Footsteps. Enough. Nauman sometimes overloads the set—voice atop corridor, noise atop image. For Birnbaum, this tips into surplus where Beckett remains razor-thin. The contrast is instructive: Beckett builds artificial gravity by subtraction; Nauman tests tolerance by accumulation.

Late Beckett and early Nauman are contemporaries of a shared, post-disciplinary field. Their reciprocity produces the terms of influence as much as it inherits them. Repetition here is not mere return. It is inventive pressure.

Both artists stage the human as a problem of balance. Bodies lean forward, slightly falling, to keep moving. Clumsiness becomes a method. Grace is the accident of endurance. The work is ground-thinking: making time audible, space palpable, and failure productive. This is why the relation must be read across forms. The borders matter, and they do not.

— Alun Rowlands

The work of Samuel Beckett and his centenary this year is being celebrated by the University of Reading through a commissioned video work by artists Paul Harrison and John Wood.

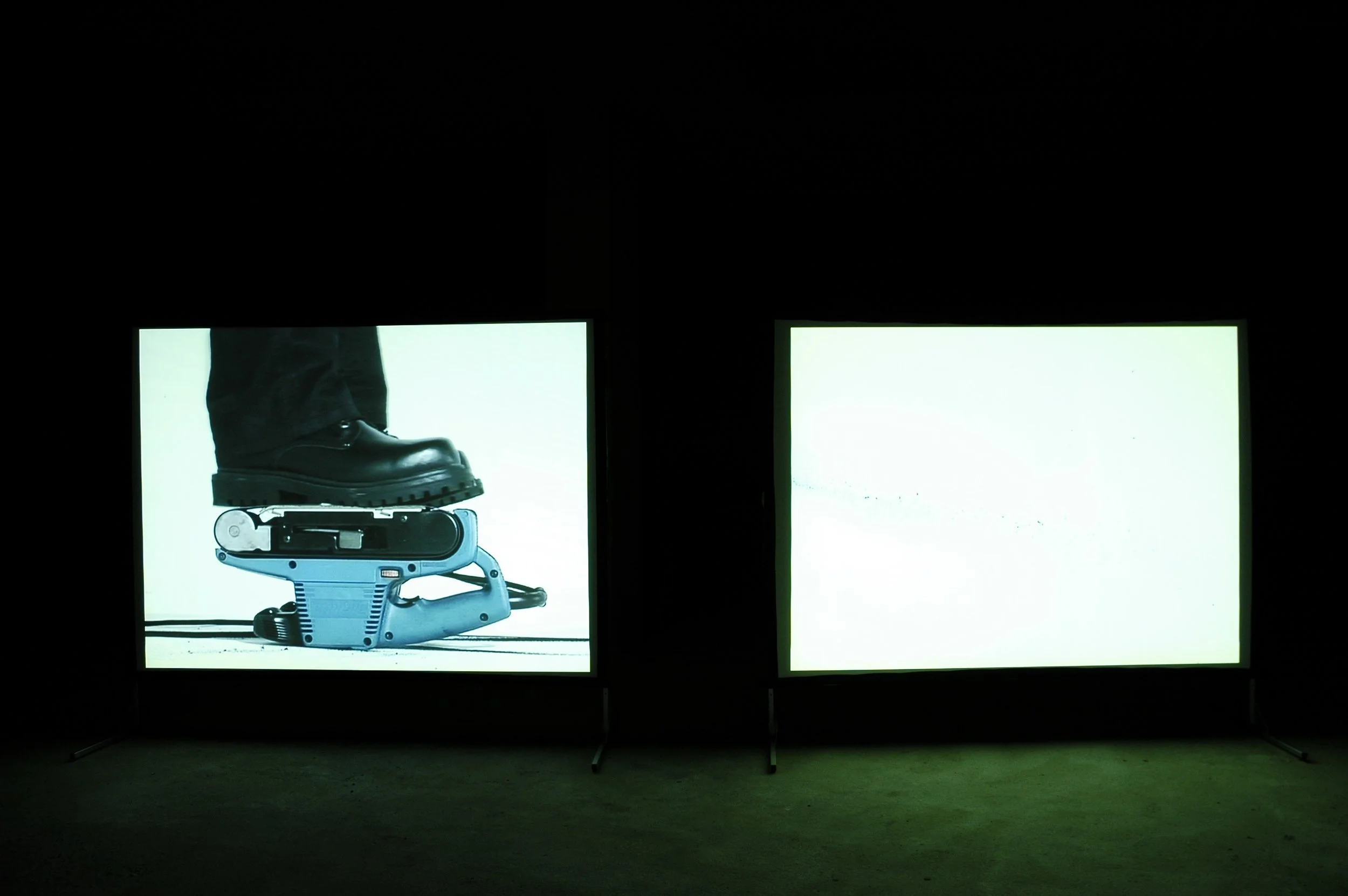

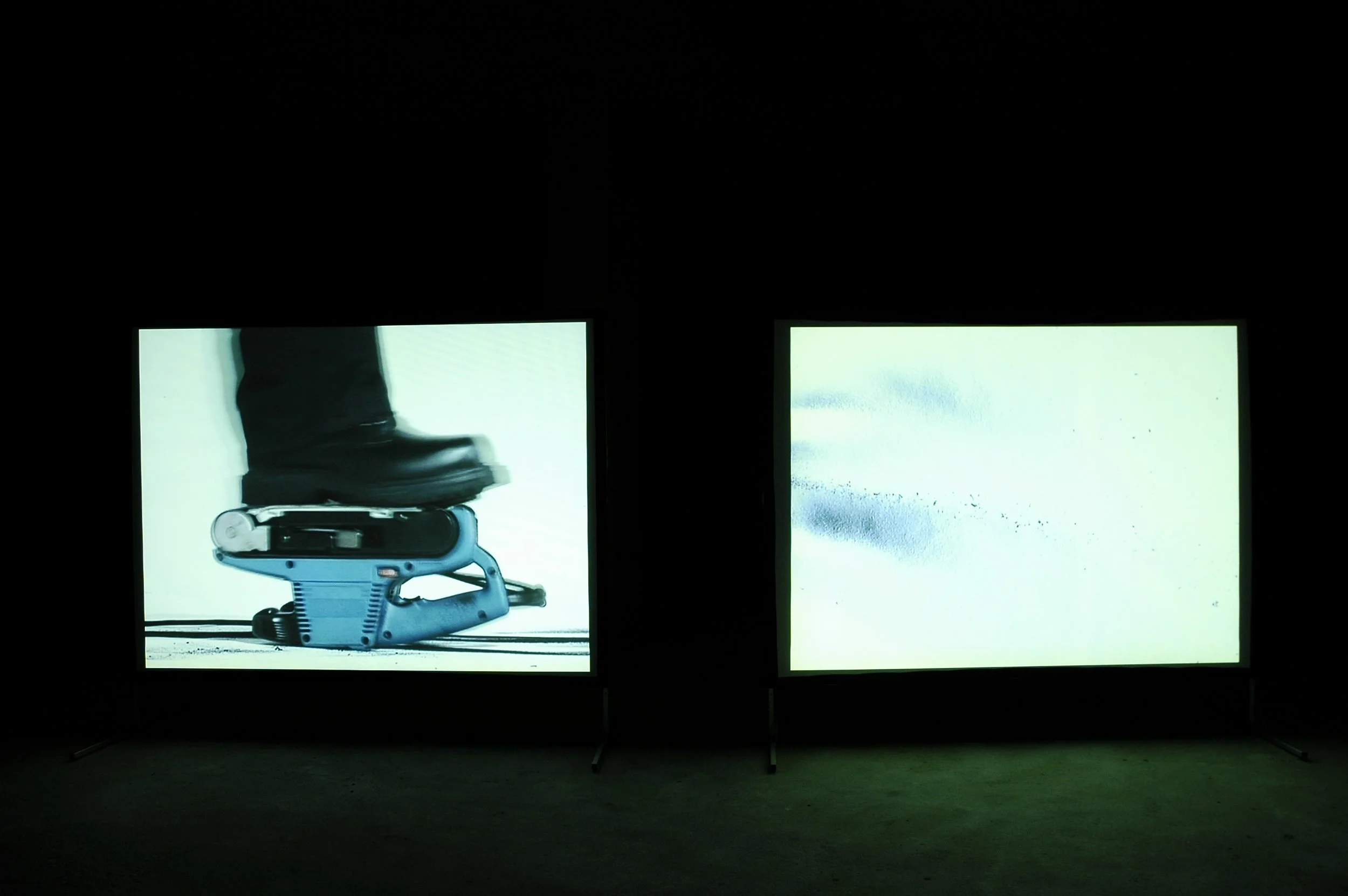

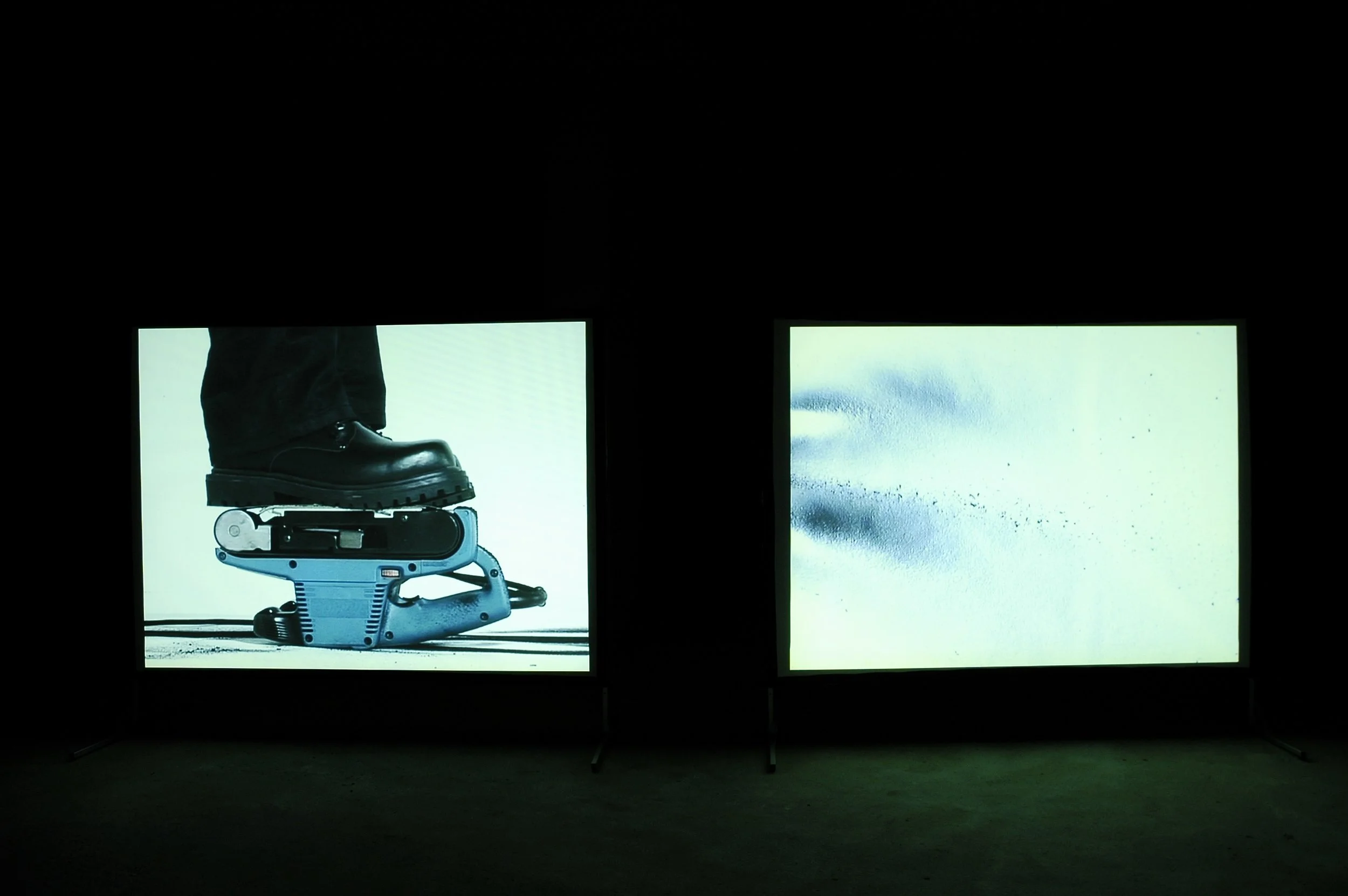

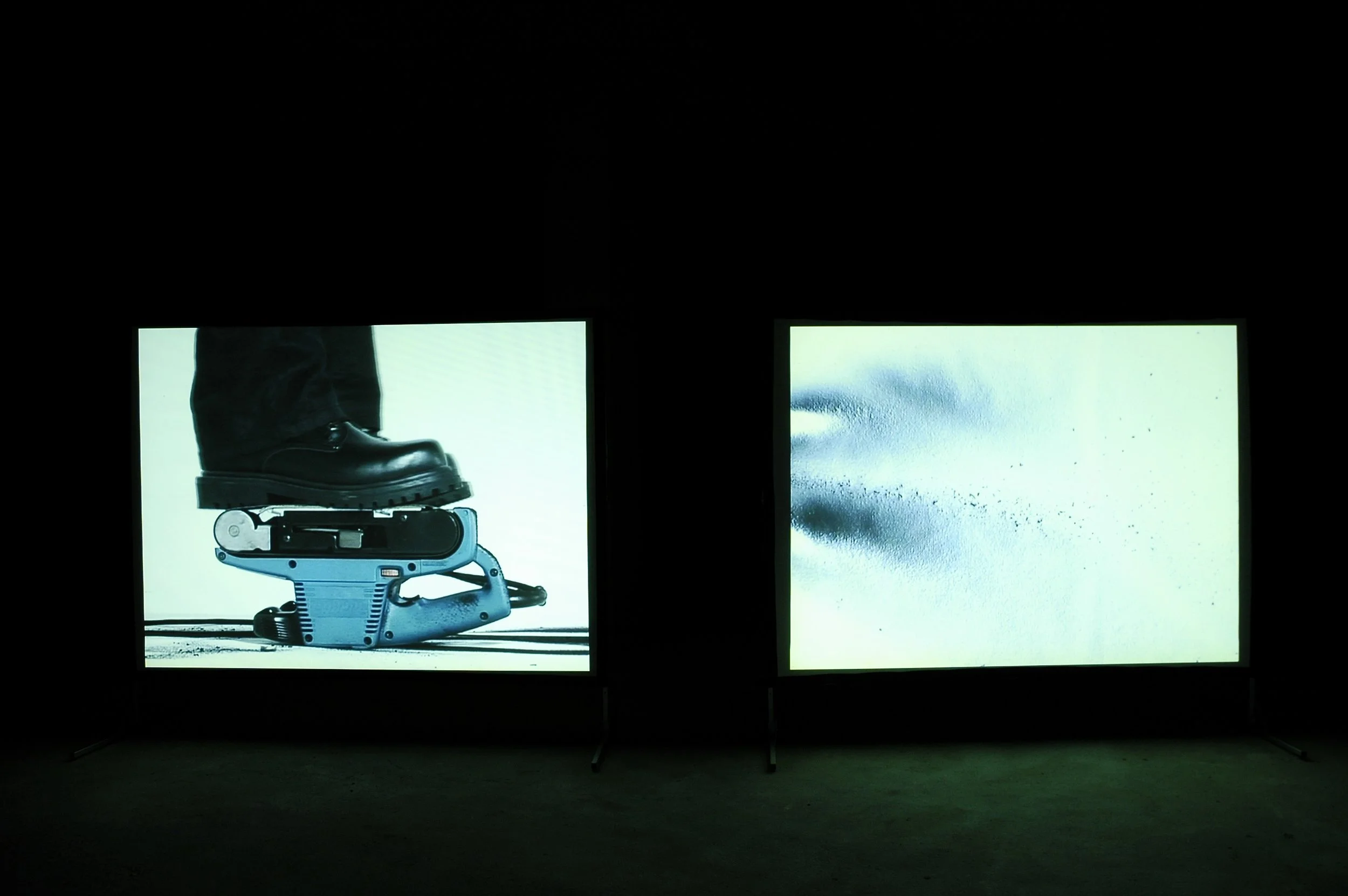

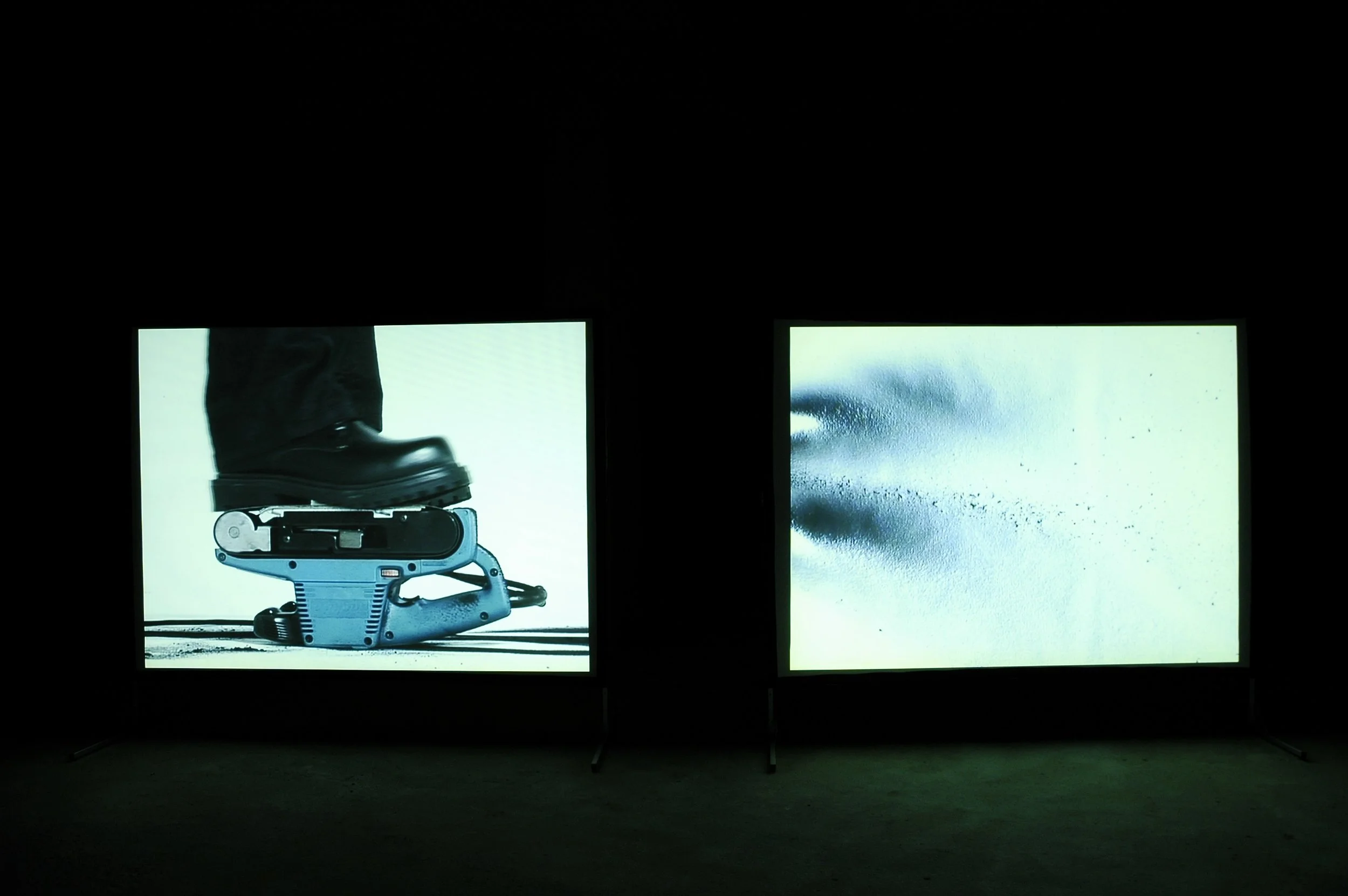

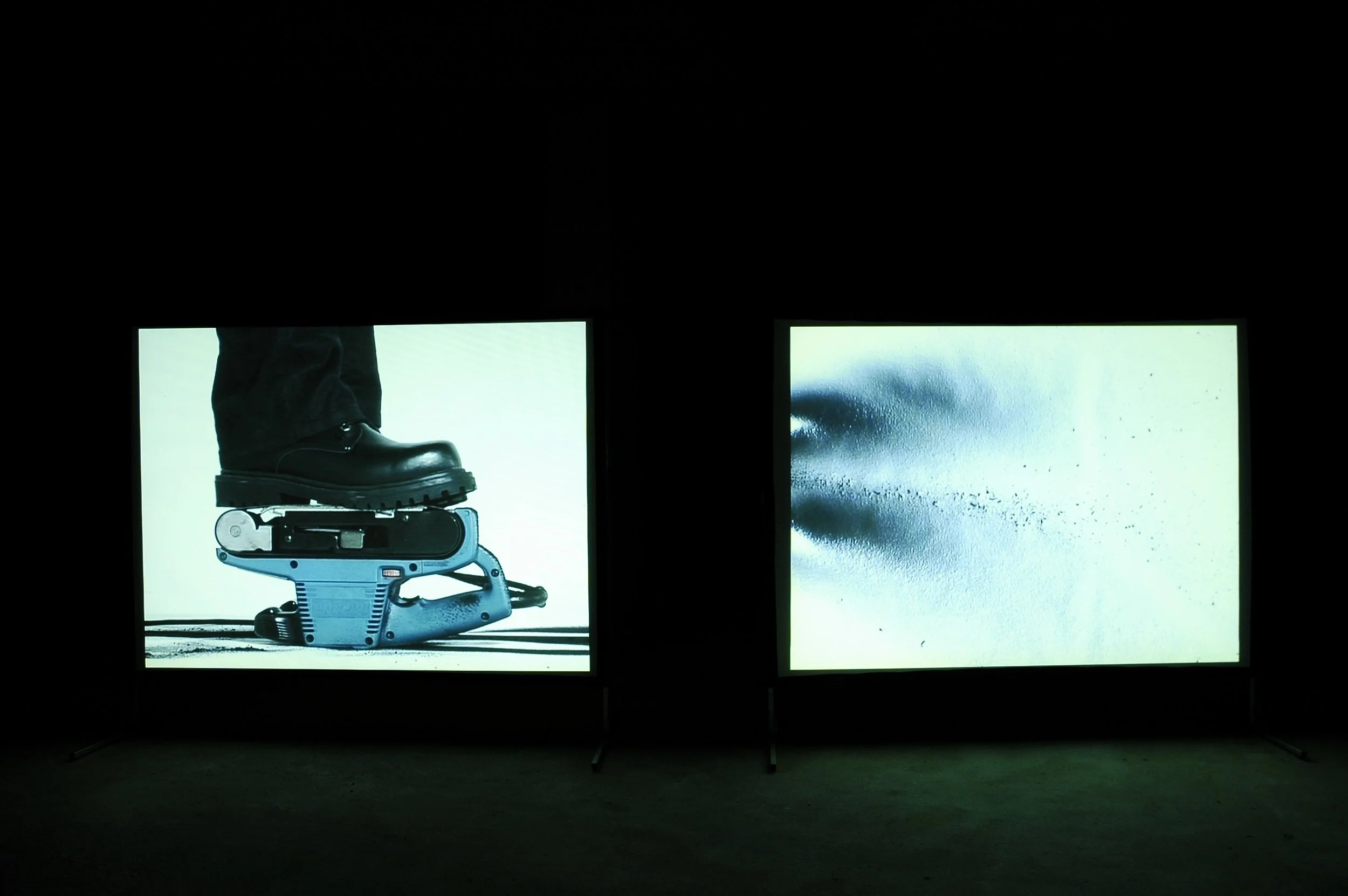

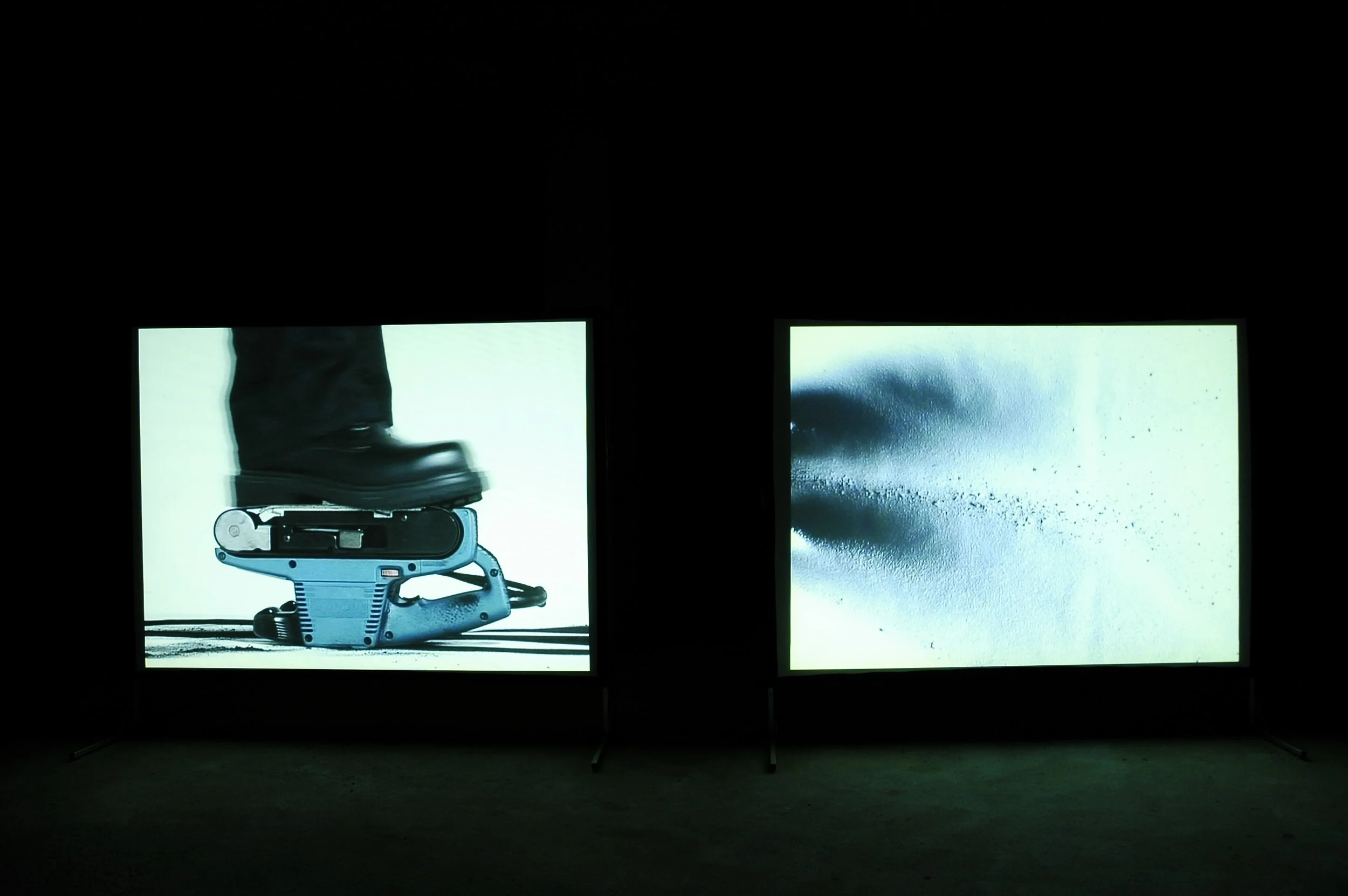

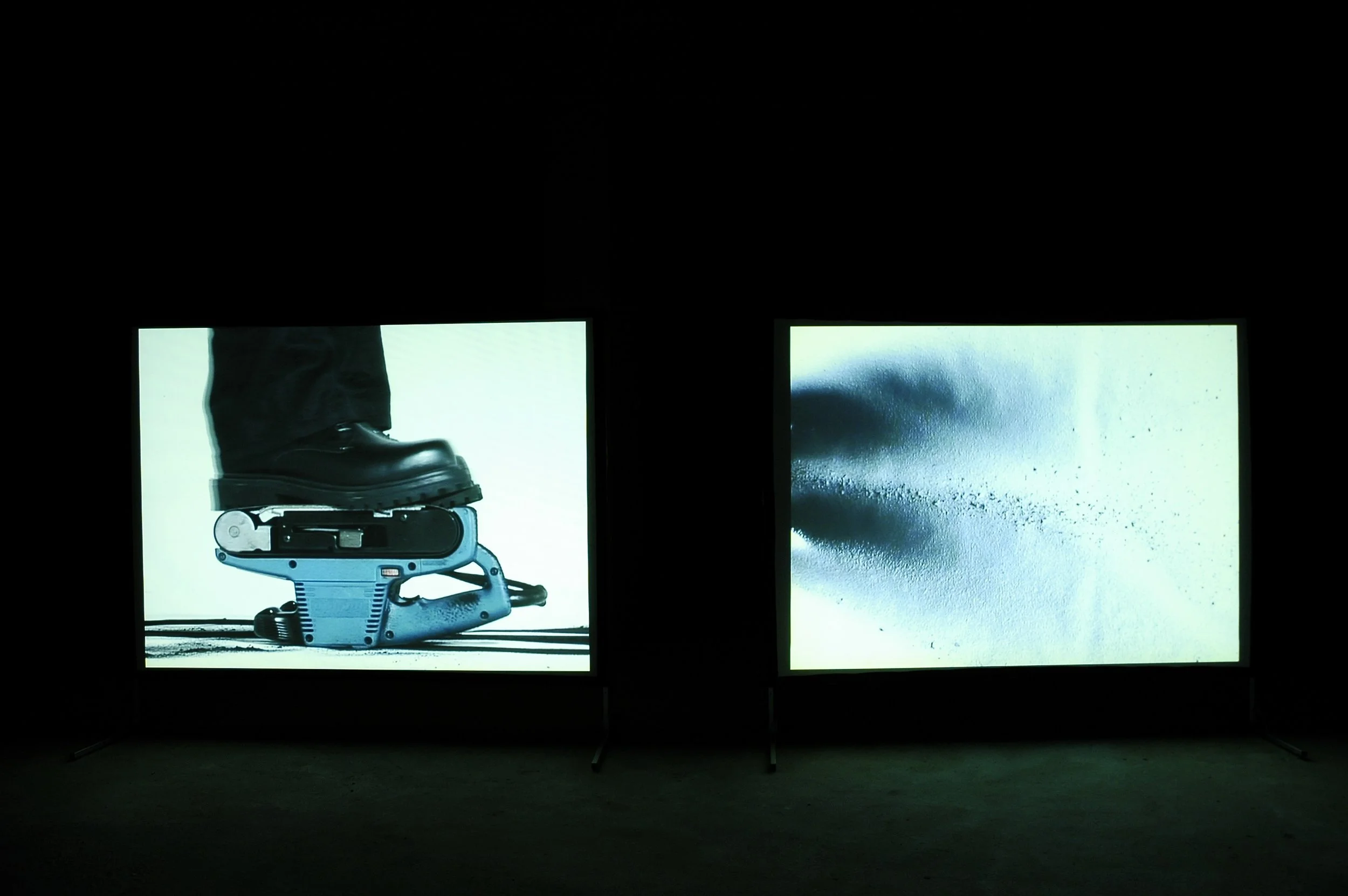

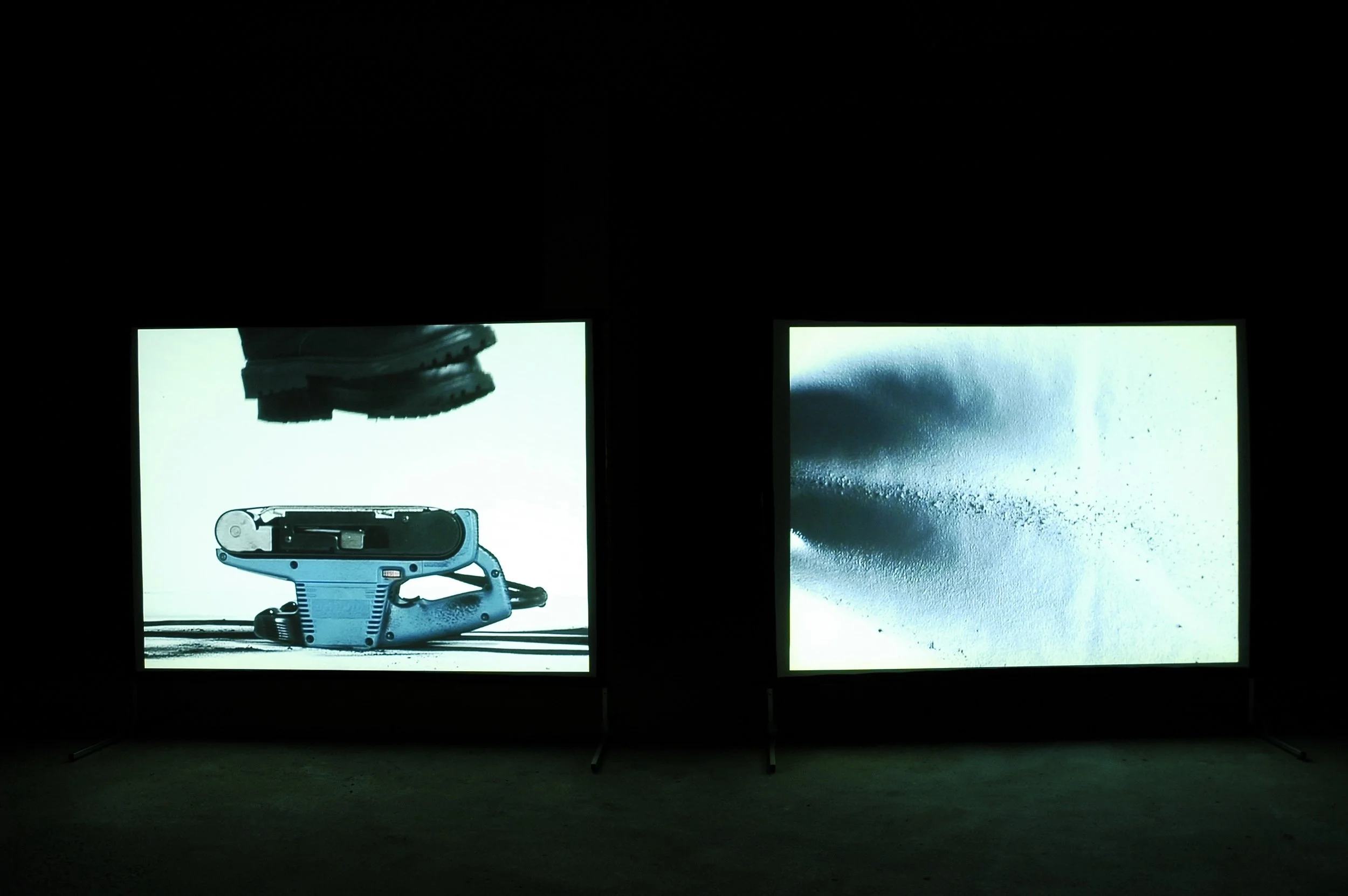

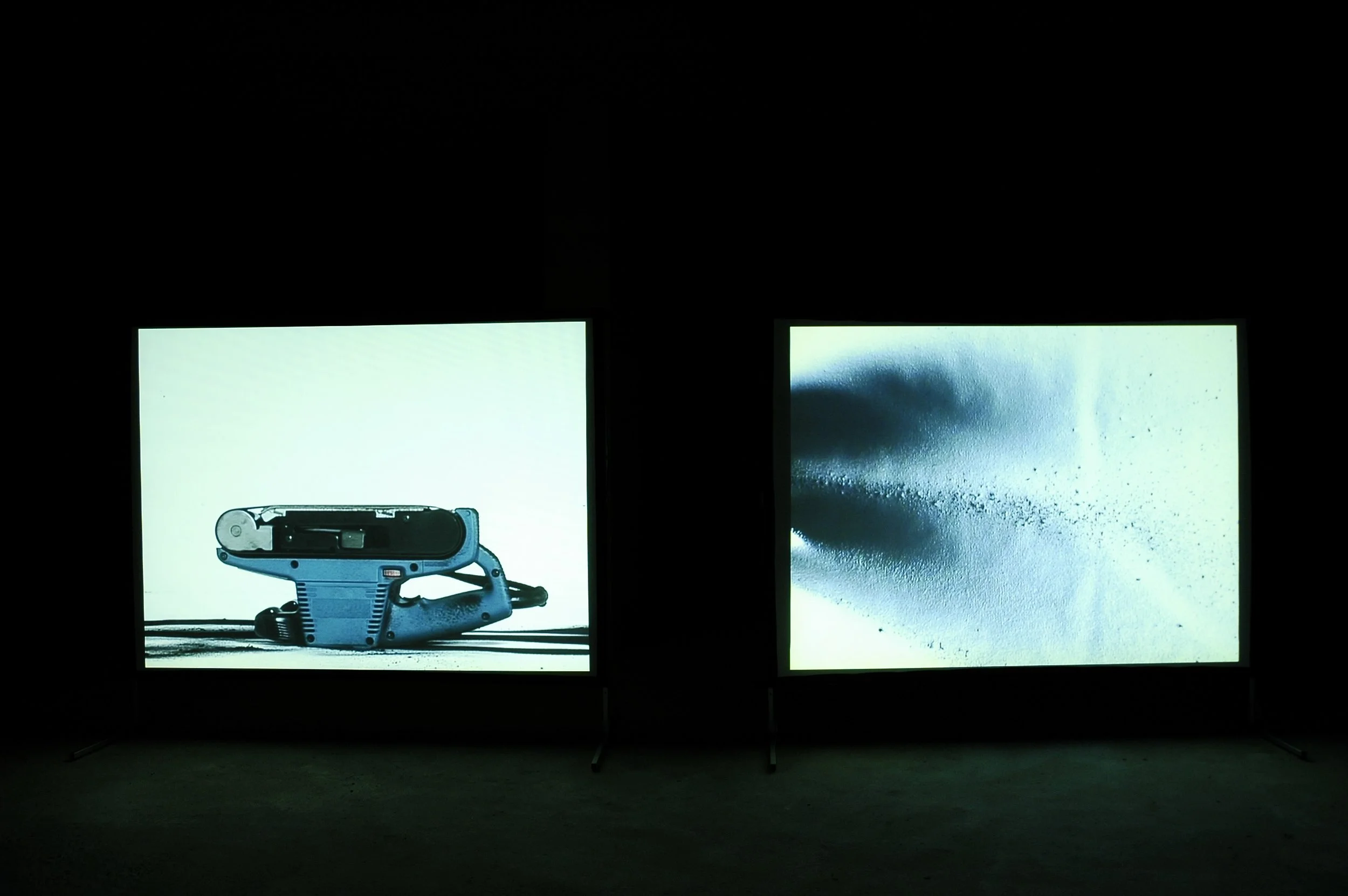

Another pair is a two-screen work which examines human interaction and our fascination with the properties of everyday objects. Another pair takes its title from Beckett's short story ‘The End’ (1946). The story's protagonist shares the preoccupation that Harrison and Wood have for the absurdity of creative activity. Acknowledging Beckett as an important influence on their practice, Harrison and Wood's work explores the nature of the 'work' of art.

The documentation of the commission will reside long term and be made publicly available within the Samuel Beckett Archive housed at the University of Reading.

The project is supported by the Arts Council of England and is being held in association with Artists in the City and the support of Stonemartin Corporate Centres.

John Wood and Paul Harrison have worked together since 1993 producing video works for single screen and installation. They are represented by f a projects, London. A major monograph of their work, 124 minutes, has been published by Ffotogallery, Cardiff. Recent exhibitions include: 5 Rooms - Ludwig Museum, Budapest 2006 Les Mouvement des Images- Centre Pompidou 2006 You'll Never Know- A Hayward Gallery Touring Exhibition 2006 Supernova- A British Council Touring Exhibition 2005 Selected Tapes- MOMA New York 2005.

University of Reading marks the centenary of Samuel Beckett’s birth with According to what? an exhibition of works by Bruce Nauman. Samuel Beckett’s influence runs through Nauman’s practice, both share a fascination with the body, space, and the fundamental questions of the human condition. Hosted by the Museum of Reading, the exhibition situates six monitor-based video works in carefully negotiated sites that resonate with the museum’s permanent collection and displays.

Slow Angle Walk (Beckett Walk) 1968 shows the artist walking, ‘stiff-legged’, back and forth in his studio. His movements follow strange undisclosed rules of steps and numbers. Nauman, as the title suggests, seems to be adopting the compulsive behaviour of Beckett’s protagonists Watt or Molloy. Beckett and Nauman’s practices converge within performance. Bouncing in the Corner 1968 is strangely choreographed attempt to levitate. Wall floor postions 1968 sees the artist performing curious exercises squatting, stamping, and lying in an absurd comic moment. Nauman’s demeanour and actions reflect on the futility of creating something, anything, in an empty white space.

Whereas Beckett used the platform of the stage Nauman turns the situation around drawing the line of the stage around himself and then the viewer. He creates mental spaces that examine, like Beckett, the futility and exhaustion of their respective art forms. All extraneous ornamentation has been eradicated to create a reality of bodies in spaces and states of experience that are more than realistic and utterly disillusioning.

Slow Angle Walk (Beckett Walk)

1968, 60 min, b&w, sound

A fixed camera turned on its side records Nauman repeating for nearly an hour a laborious sequence of body movements inspired by passages in works by Samuel Beckett that describe similarly repetitive and meaningless activities. Hands clasped behind his back, he kicks one leg up at a right angle to his body, pivots forty-five degrees, falls forward hard with a thumping noise, extends the rear leg again at a right angle behind, and begins the sequence again. As in many of his fixed-camera film and video works, parts of Nauman's body disappear from the frame as he moves close to the camera; occasionally, he walks off-screen completely while the sound of his footsteps continues on the sound tracks.

Walk with Contrapposto

1968, 60 min, b&w, sound

Nauman focuses his video camera down the length of a long, twenty-inch corridor, which he built in his Southampton studio expressly as a prop for the videotape. With his hands clasped behind his neck and swinging his hips, he animates a classic contrapposto pose as he walks up and down the length of the corridor. "The camera was placed so that the walls came in at either side of the screen," he explained. "You couldn't see the rest of the studio, and my head was cut off most of the time. ... In most of the pieces I made [in 1969] you could see only the back of my head, pictures from the back or from the top."

Bouncing in the Corner No. 1

1968, 60 min, b&w, sound

For this videotape, Nauman turned the camera sideways and positioned it so that his head is cropped from the frame and his body is presented from neck to ankles. As he stands in the corner, his back to the wall, he appears to be lying down; falling backwards into the corner and then pushing himself off the wall again, he appears to be trying to levitate himself... As he performs these actions, his hands slam into the wall to break his falls, and the sounds become an integral part of the activities filmed.

Revolving Upside Down

1969, 61 min, b&w, sound

A stationary camera set upside down and framing a long shot of the studio records Nauman, with his hands clasped behind his back, repeating a series of steps similar to those of Slow Angle Walk (Beckett Walk). The curious exercise combines pirouettes, goose steps, and crabbed, angled arabesques. The inverted image further disorients our sense of the maneuvers, which appear to be taking place on the ceiling.

Wall-Floor Positions

1968, 60 min, b&w, sound

In this videotape Nauman assumes a set of positions in relation to a wall and floor similar to those he had executed for an untitled 1965 performance, which he described as "standing with my back to the wall for about forty-five seconds or a minute, leaning out from the wall, then bending at the waist, squatting, sitting, and finally lying down. There were seven different positions in relation to the wall and floor. Then I did the whole sequence again standing away from the wall, facing the wall, then facing left and right. There were twenty-eight positions and the whole presentation lasted an hour."

Stamping in the Studio

1968, 62 min, b&w, sound

For this work, Nauman pounds out rhythms with his feet that increase in complexity as he paces his studio, beginning with a steady one-two beat and advancing to a syncopated ten-beat phrase. As he stamps back and forth across the studio, he moves diagonally and in spirals. The camera is upside down, and the action is thus inverted in the frame.

Bruce Nauman is one of most influential figures in contemporary art. His films and videotapes from 1968 rank among the most innovative experiments using his own body as an object of inquiry, executing repetitive, studio-based performances.

The exhibition is an opportunity to consider Nauman’s work in dialogue with Samuel Beckett. The six videos selected exploit the immediacy and intimacy of space coupled with gesture that investigate games, rituals, dance, spectacle and the very process of making art. The exhibition will open up the museum into a performative stage that reflecting on the legacies of both Samuel Beckett and Bruce Nauman.