ABC: A Browser for a Speculative Collection

Rowlands, Alun. ABC: Browser for a Speculative Collection. Originally published in ‘The Shape We’re In’ London - New York, 2011, edited by Ellen Mara De Wachter, p.122 - 128, ISBN 0-9703955-6-6

The Shape We're In (London) includes works by Martin Boyce, Ethan Breckenridge and Sean Dack, Rachael Champion, Matthew Darbyshire, Matthew Day Jackson, Nicolas Deshayes, Samantha Donnelly, Sean Edwards, Peggy Franck, Ryan Gander, Fergal Stapleton, Haim Steinbach, Jack Strange, Nicole Wermers, Franz West.

A second London-based exhibition, The Shape We're In (Camden), sees works by Tracey Emin, Dan Attoe and Jack Strange installed in vacant shops around the London borough of Camden.

The Shape We're In (New York) is an exhibition of works from the Zabludowicz Collection featuring new commissions by Sarah Braman, Ethan Breckenridge, Sean Dack, and Nick van Woert.

Curated by Ellen Mara De Wachter

This essay writes the collection as a browser—an assemblage of fragments, citations, and conjectures in motion. It treats collecting as a linguistic and epistemic act: speculative, recursive, unstable. Summoning Flaubert’s protagonists, Bouvard and Pécuchet, it turns contradiction, accumulation, and failure into method. The writing performs what it describes. It copies, accumulates, and builds order only to dissolve it. Each paragraph is a search —each reference, a cached link.

Through Foucault, Latour, and Benjamin, the essay reimagines the collection as a field of relations rather than a container of objects. It advances an undisciplined mode of writing that mirrors the heterogeneity of the contemporary art collection—restless, provisional, always beginning again. The result is both a reflection on collecting and a speculative collection of its own—a text that reads by rewriting.

— Onward! Enough speculation! Keep on copying! The page must be filled. Everything is equal, the good and the evil. The farcical and the sublime-the beautiful and the ugly-the insignificant and the typical, they all become an exaltation of the statistical. There are nothing but facts and phenomena. Final bliss. [1]

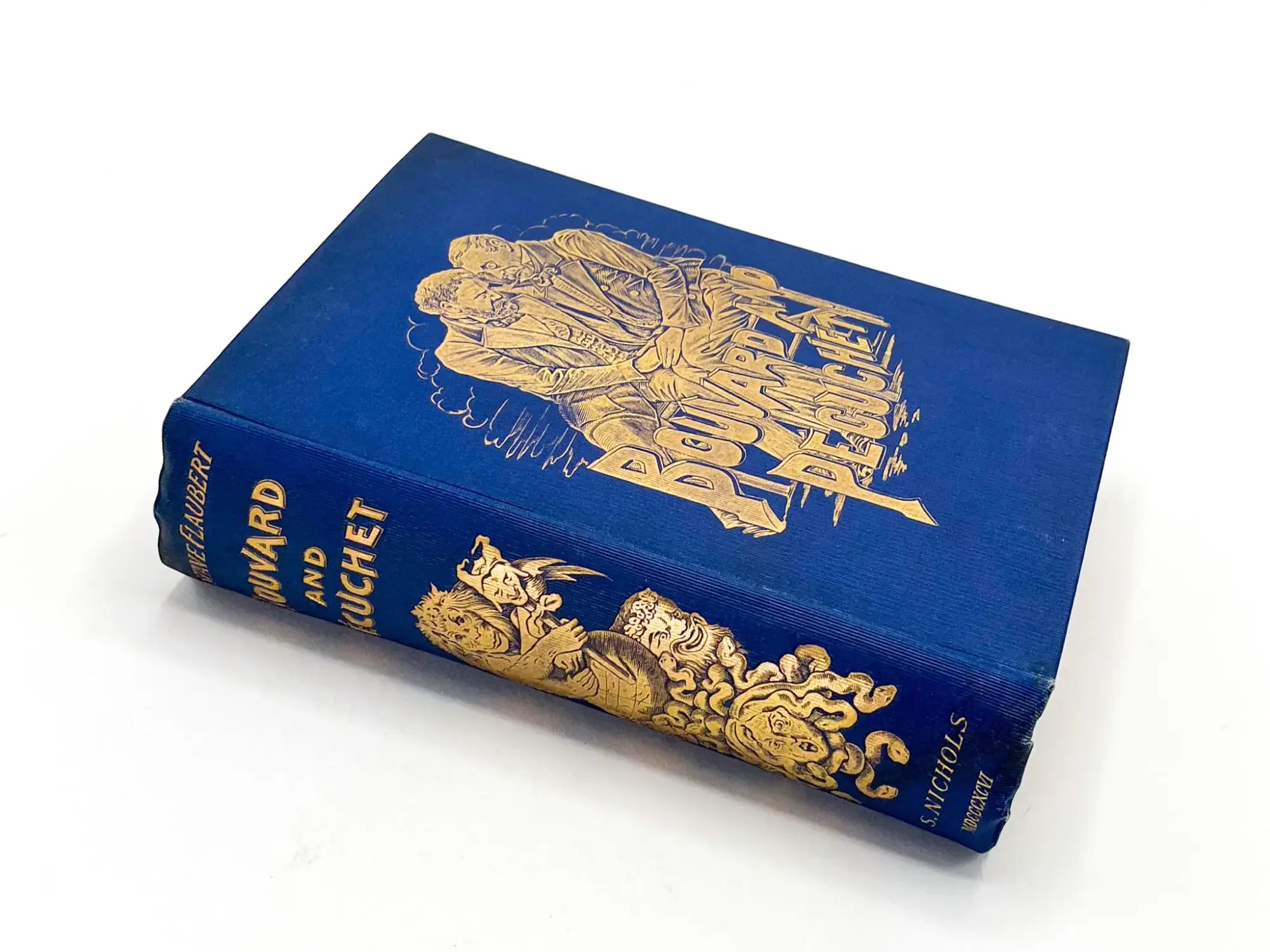

Bouvard and Pécuchet is a novel that systematically parodies the unpredictable, the inconsequential and the veritable excess of received ideas. Flaubert’s protagonists are perplexed through the assault of new knowledge, and with the societal attitudes that attend it, by acting out an authentic encyclopedia of modern pursuits. The narrative of two scribes attempting to write the whole world signifies an awkward, barely comprehensible, subversive philosophical narrative about the limits of knowledge and exegesis. In preparation for each of their ventures, they consult assorted papers and article, in which they are confounded to find contradictions and misinformation of all kinds. [2] The counsel they seek in them is either confusing or utterly inapposite - theory and practice never correspond. But, undaunted they move on relentlessly to the next activity, only to find that it too is incommensurate with the texts which purport to represent it. With poignant enthusiasm they consecutively delve into disciplines such as archaeology, geology, history, literature, politics, and religion, only to gradually fail in finding any sense encountering newly verbalized realities. When experimentation does not work, methods of trial and error engage in the explorations of theory. When they finally succumb to the fact that the knowledge they have relied upon is a mass of contradictions, utterly haphazard, and quite disjunct from the reality they'd sought to confront, they revert to their initial task of copying. [3]

Haim Steinbach, Family Ties, 2007

The series of heterogeneous activities and behaviours of Bouvard and Pécuchet may not be, as Foucault and others have claimed, the library-encyclopedia, but rather the site of a collection. An assembled collection occupies a central position in the novel; it is connected to the characters' interest in the acquisition of knowledge, origin, causality, and representation. If Bouvard and Pécuchet is a parody of received ideas then a collection of contemporary art is the hyperbole of such ideas. Collections of contemporary art are a suspicious body of knowledge, whereby collecting is a work of distance from the ecstasies of the event. Collecting contemporary art begins from an image of what it is to collect, whether that is the grasp of ideal forms, the orderly reception of sense receptions or the social construction of the world through a material language. The objects and practices of a collection both build, and build upon, that image. Any assemblage as the material vocabulary of a collection faces in two directions – ‘to assemble is one thing; to represent to the eyes and ears of those assembled what is at stake is another.’ [4] It both gives some sort of order or consistency to a life which bears much greater complexity and dynamism, but it also enables – from that order – the creation of further and more elaborate orderings. It gives sense or orientation to a world but it also allows us to produce further differences and worlds. There is a necessary fidelity and infidelity that leads us to the sense of art which can only be given through the production of another work, text, object... To work with a collection through its vagaries is to understand the problems that motivated its assemblage. If the history of collections is a gallery of such images then some assemblages have done more than stroll through this gallery to add their own image. Some have schizophrenically refused to add one more proper relation between object and thought and have pulled things apart.

Martin Boyce, Telephone Booth Conversations, 2006

‘We simply stopped thinking of ourselves as a 19th Century museum... And more on instituting – in the ancient sense of the word - of founding and supporting. On instituting creative practice. So, we started to play, risk, cooperate, research and rapidly prototype... And that’s how we devolved locally, and networked globally.’ [5]

What if the collection itself were to proliferate? No matter how much we assert ourselves through trope or method. We need a storehouse or archive that profligates itself, to raise the voices of alternative communities to extend potential. How is this done? A fragmentary project, blogs, threads, papers, possibilities, circulating in a refusal of narrative or theoretical completion. In the process, weakening the voice of authority, suggesting we are constantly moving toward understanding, toward that which has potential. What is required is a browser to cache a multitude of searches adding behaviours to a richer textual field. Browsers are compasses of alphabetical systems; the drama expands horizontally revealing the routes of an imaginary narration. Alphabets construct order. An order which unfolds along the sequence of a limited number of letters but at the time opens up the potential to propagate. The alphabet is an order without meaning, an exemplary order, which is able to link the singular with the general. The alphabetical order of words eludes demonstrative or thematic arrangements and polarising situations. Indeed a ‘Dictionary of Received Ideas’ was to comprise part of a second volume of Flaubert's last, unfinished novel. A fiction that addresses the unreliability of the interpretive medium versus the notion of an unreliable narrator alongside unreliable protagonists, and unreliable reader, respectively. None of the characters are to be taken by their words easily since they are located off the chart of suitable exegesis, and persistently follow erroneous directions. So it might seem a distinctly craven, literal minded and reactive project to forge a browser, or dictionary for a collection. But this would be an open process in which we can and need to intervene; at the same time, the aim would be to develop maps that redefine the material of a collection not from an interdisciplinary perspective but rather an undisciplined approach, developing collaborative processes.

Nicole Wermers, Untitled Bench, 2008

This hodological approach browses a possible genealogy for contemporary art practice and its institutions, through vividly re-imagining the collection. It takes place through the unfolding methods among an ensemble of collaborative agents. The locus of creative production is displaced from the level of independent ideation on the part of the collector to an indeterminate collectively authored exchange among multiple interlocutors. A collection of contemporary art strategically avoids a lexicon and the notion that disparate works corralled together purely through the pronoun of the named collector, might simply name extra-textual truths. It also rejects the idea that art could be understood without a sense of its specific creative problems. Such a collection produces connections and modes of material thinking. To translate these works or to define any point in the collections corpus involves understanding a more general orientation, problem or milieu. This does not mean reducing a collection to its contexts – on the contrary to understand performative philanthropy as the creation of a plane, or as a way of creating some navigational points and relations, means that any collection is more than its manifest terms, more than its context. We invert Walter Benjamin’s, relationship between collecting and libidinous desire, the primal collecting urge that attempts to reclaim the old world whereby the object must be released from its function, taken out of the bondage of use and circulation, reborn in the privacy of the collection. The whole business is intense and obsessive. It maximises the oddments of knowledge, and acknowledges the embarrassment of discursive nudity. Free from any commitment to any fixed audience it is a transitive endeavour; transitive through affinity for the possibility of a community. The immateriality of the collection in circulation not only secures the permissions of objects, outcomes of practice, to the expanded notion of the collection, it is also the categorical principle. Wrestling difference away from a single perfect similitude into the singular plural of a common-ism; from the I to the you to the we.

Sarah Braman, Ghost Sculpture (Coffin), 2010

‘As the temporary museum didn’t know what to say to this, another day and half of the next day passed without a word being passed between the moon and the museum. Finally the museum made up her mind and said: “All my life I have had to present myself in public knowing that I am a mere shadow of the building that was originally planned. My masters always dreamed of a much grander more elegant design. I came to be only when this was no longer possible. You see it was only out of desperation that I was built and, I am still only temporary. My walls are well enough made but it burdens me to live with this knowledge.” [8]

Accumulating around the staged exhibitions and events, and in addition to the unequivocal historical conjecture, there is an outthought - the problem, desires or life of a collection. Methodological problems – track the occurrences – intermittent, occasional, gradually insistent, then suddenly ubiquitous – of ideas within contemporary art. All of this enfolds within the collision of a number of associative and affiliative contexts; our self-institutionalisation and location are shaped by history and education. A situation in which knowledge can be accessed from distributive networks. Networks care neither for significance nor consequence. A community of practice, expansive behaviours, which demand more participants and different speeds of thought – ‘that’s where the slowing down comes in – you can create new habits only by slowing down, because new habits also mean new feelings, new interests, new possibilities...’ [9] Examining the future trajectory of a collection requires going beyond his or her produced lexicon to the extended common-sense of production from which the relations or sense of the works emerge. This sense itself can never be said, in repeating or recreating the milieu of a collection, all we can do is produce another sense, another said.

Bouvard and Pécuchet maintain the heterogeneity of artefacts, which defies the systematization that knowledge demands. The set of object-practices that a collection displays is sustained only by the fiction that they somehow constitute a coherent representational universe. The fiction is that a repeated metonymic disarticulation of fragments can still fissure a constellation which is somehow adequate to a non-linguistic universe. Such a fiction is the result of an uncritical belief in the notion that taxonomy and cataloguing, that is to say, the spatial juxtaposition of fragments, can map understanding of assembled forces —‘the role of creating a space of illusion that denounces all real space, all real emplacements as being even more illusory’. [10] Should the fiction disappear, there is nothing left of the collection but ‘bric-a-brac’ a heap of meaningless and valueless fragments which are incapable of substituting themselves either ‘metonymically for the original objects or metaphorically for their representations’.[11]

This perception of the collection is what Flaubert figures through the comedy of Bouvard and Pécuchet . The faith in the possibility of ordering the collection’s assemblage through a fiction. This fiction is the imaginative writing fuelled by conjecture - scenario driven promissory notes – the ‘what next?’ Speculation, the subjunctive tense, the ‘as yet’ question that drives behaviours and actions as if we know that we would be here tomorrow. Speculation overwhelms aesthetics; it is the dominant trope or behaviour of recent years, a vague reckoning of both social and economic models. Speculation demands to speculate on its possibility and potentiality as self-referentiality, in the sense that it ‘creates’ that which it speculates. The spectral inheres the act of speculating, dealing with a precise stupor, a limitless potentiality ‘in the mirror of what it produces’.

In and through a speculative dialogue, progress is possible – while the artworks housed within the collection can perhaps only maintain an inaudible hush. What emerges from alternative outlets, threaded discussions and cached searches is a panicked episteme. Part theory, part fiction, intervening in the general forms of visibility, assembled so smoothly we cannot see the joins. Not so much collecting as the coalescent forces arising from a ‘parliament of things’. We do not theorise, we secrete the seams, an interstice not only for fiction and theory but also for events in the process of capture and escape – ‘art like gossip, reportage or social life ‘produces’ knowledge – it discloses communicable truths about itself, about artists or most dramatically, about the world.’[12]

— Alun Rowlands

[1] One of Gustave Flaubert's possible endings for his novel Bouvard and Pécuchet (1881), as cited by Douglas Crimp, "On the Museum's Ruins," The Anti-Aesthetic, Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend, Washington: Bay Press, 1983) p. 48

[2] “How much do we have to study to liberate ourselves from books, and how many do we have to read! What is left to us is to drink the whole oceans, and urinate them back again” Flaubert, Gustave (Dopisy, Praha: Mladá Fronta, 1971) p.221

[3] ‘As regards the men and events of the period, they no longer had a single solid idea. To judge impartially they would have had to read all the histories, all the memoirs, all the journals, and all the manuscript documents, for the slightest omission may cause an error which will lead to others ad infinitum. They gave up’. —Flaubert, Gustave Bouvard and Pécuchet, (London: Penguin Books, 1967/1881)

p. 121.

[4] Bruno Latour, Realpolitik to Dingpolitik, or How to Make Things Public, MIT 2005

[5] Neil Cummings, Museum Futures: Distributed 2058 transcription, 2008

[6] Jan Verwoert & Michael Stevenson, The Moon and the Temporay Museum, 2008

[7] Isabelle Stengers, A Cosmo- Politics’ Risk, Hope, Change, 2002

[8] Douglas Crimp, "On the Museum's Ruins," The Anti-Aesthetic, Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend, Washington: Bay Press, 1983)

[9] Will Holder, Ann Demeester et al. Editorial from F.R David, de Appel arts centre, Amsterdam, Spring 2007